Latin American Art 20th Century

Permanent collection

MALBA Fundación Costantini, in its dedication to 20th century Latin American art, owns a unique collection that includes the principal tendencies and movements that characterize the region’s art in all its mediums, bringing together paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings, collages, photographs, installations and artists’ objects from Mexico and the Caribbean to Argentina.

Since its opening to the public in 2001, one of the museum’s principal institutional objectives has been the permanent display of most of its artistic patrimony, offering to visitors innovative lectures and different approximations to the history of art in Latin America.

Since the first modern and avant-garde movements to the more contemporary productions of the late 20th century, the collection’s exhibition varies according to the dynamics of the Annual Program of Acquisitions and to the generous donations received from artists, their family members, and private collectors.

Modernism | Avant-Garde

Starting in the early 20th century, Latin American artists traveled to Europe, where they came into contact with avant-garde movements and developed artistic proposals bound to Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism. They were active participants in major exhibitions and debates in cities like Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Berlin, Florence, and Milan. Their works and writings asserted the autonomy of art and eschewed painting and sculpture as means of representing reality. In the twenties, many Latin American artists who lived in Europe returned to their countries of origin to become major players on local art scenes embroiled in the battle between the traditional and “the new.” Xul Solar’s Neocriollism (Buenos Aires), Tarsila do Amaral’s Anthropophagia (São Paulo), as well as Rafael Barradas and Joaquín Torres-García’s Vibrationism and Constructive Universalism (Montevideo), are only a few examples of the avant-garde movements that emerged throughout Latin America.

Art and Politics | Modern Photography

In the thirties, the connection between art and politics was crucial on both regional and international levels. From murals by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros (Mexico) to paintings by Antonio Berni (Argentina) and Candido Portinari (Brazil), artists discussed and formulated new relationships between artistic expression and its social context. Artists engaged in collective work, political activism, and debates that gave rise to varying forms of Social Realism, Nativism, Nuevo realismo, and critical art, mostly in painting and graphic media. Photography, film, and press coverage of current events and regional political instability were the sources of visual production. Images of rural and urban workers, as well as figures protesting or engaged in traditional celebrations, begin to appear in often monumental pictorial works. Representations steeped in local references made use of materials and expressive and technical resources that gave artistic expressions a social dimension. Burlap from a potato sack or tempera paint of the sort used in murals were often chosen by politicized artists. The medium of photography was integral to a local art scene with renewed energy, one concerned with documenting frenetic modern life and the growth of cities.

Strains of Surrealism

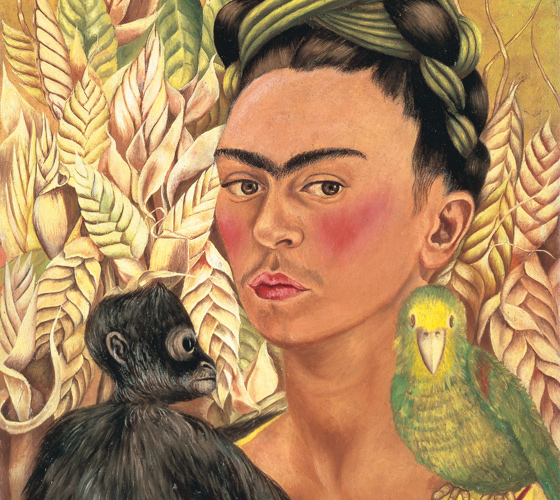

Starting in the twenties, many Latin American artists investigated the worlds of magic and fantasy, creating images related to their life experiences and religious beliefs or, in some cases, to the Surrealist movement which was spreading around the globe. This literary and visual movement explored the fields of psychic energy. It eschewed the intervention of the conscious by means of practices like free association and psychic automatism, as well as the use of chance. To encourage the emergence of the unconscious, these artists would resort to techniques that yielded unusual effects and uncontrollable processes, like photomontage, collage, frottage, decoupage or sgraffito. Works by Antonio Berni, Juan Battle Planas, Maria Martins, Cicero Dias, Roberto Matta, Frida Kahlo, Agustín Lazo, and Wilfredo Lam display the diverse effects of these techniques as well as the intersection of popular traditions and the high art circulating in the region at the time.

Concrete and Neo-Concrete Art | Op and Kinetic Art

In the early 20th century, abstract and non-figurative tendencies emerged to become part of international art history. These movements rejected the illusionist premise of painting as a “window to the world” as they explored ways to free the visual arts from the representation of reality. In the mid-forties, Buenos Aires became an active center of Concrete Art and its variations. Madí, Asociación Arte Concreto Invención, and Perceptismo were the three groups formed by Argentine artists Gyula Kosice and Enio Iommi and Uruguayans Rhod Rothfuss and Carmelo Arden Quin, among others. These organizations contributed to both the production of Concrete art and the international debate surrounding that movement. Concrete artists made use of the material elements of visual language such as form, color, line, and plane as they replaced the traditional octagonal frame with irregular and unevenly- cut frames. They investigated the function of layers of color and systems of serial structures. They invented articulated and transformable “sculptures” and used industrial materials like enamel, glass and bakelite. They produced object-paintings mounted on walls and aerial mobiles hanging in space. In Caracas in the fifties, Alejandro Otero painted his series of white abstractions with chromatic lines, while Brazilians Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark turned color and light into physical bodies that take shape before the viewer’s eye. In the fifties and sixties, Julio Le Parc and Abraham Palatnik constructed artifacts that investigate the physical and perceptive experience of sight in works that included real or illusory motion and the active participation of the viewer, furthering the possibilities opened up by Op and Kinetic art.

Strains of Informalism | Destructive Art | Other Figurations | Pop Art | Objects | Minimalism | Conceptual Art

In the late fifties, the visual arts underwent a rapid transformation as modernism came to an end and contemporary art emerged. Critics and artists spoke of “the death of painting” and “the death of art.” With the advent of a new era, painting and sculpture no longer presided over the “fine arts.” New disciplines, media, and materials appeared: objects, constructions, performances, bricolages, ensembles, happenings, installations, videos, environments, interventions, and tours of spaces. “Works of art” no longer looked like “works of art” and artists began working with everyday and industrial objects, waste and discarded materials, texts and words. They embarked on actions in urban or natural settings and produced film and photographic registers. They proposed corporeal and sensorial experiences. Ever-emerging ideas and concepts mixed with Neo-Figurative poetics, Pop Art, Minimalism, Neo-Surrealism, and geometric tendencies. A radical discussion of issues like the de-materialization of the work of art and the relationship between art and politics ensued. The Latin American scene developed its own agenda, evident in production that, though sometimes tied to international Neo-avant-garde movements, always makes reference to its own cultural, historic, and social concerns. Key proponents of these tendencies included Antonio Berni, Jorge de la Vega, Antonio Dias, Fernando Botero, Nelson Leirner, Rubens Gerchman, Mira Schendel, León Ferrari, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Clark.

Strains of Conceptualism | Hyperrealism | The New Image

The last two decades of the 20th century witnessed a significant democratization of the artistic field as the notion of the “artistically correct” was eschewed. Without the prior models and knowledge that once regulated the field of art, contemporary artistic production circulated more quickly as countless possibilities arose and languages crossed and “contaminated” one another. Conceptual art had dismantled the idea of the work of art as a material presence and merchandise. Industrial materials, scientific models, reflections on psychoanalysis, linguistics, cultural studies and the mass communication all intervened in the visual arts. Works by Antonio Seguí, León Ferrari, Liliana Porter, Víctor Grippo, Waltercio Caldas and Gego exemplify these influences. Starting in the early eighties, the impact of the international return to painting made itself felt on the region’s art scenes. Thanks to the Italian Trans-avant-garde, American Bad Painting, and Latin American Neo-Figuration—and the New Image in Argentina—large canvases with images that combine the codes of film, theater, literature, music, dance, urban graffiti, and gender studies began to circulate internationally. Two actors key to this “resurrection” of painting are Argentine artist Guillermo Kuitca and Cuban artist José Bedia.