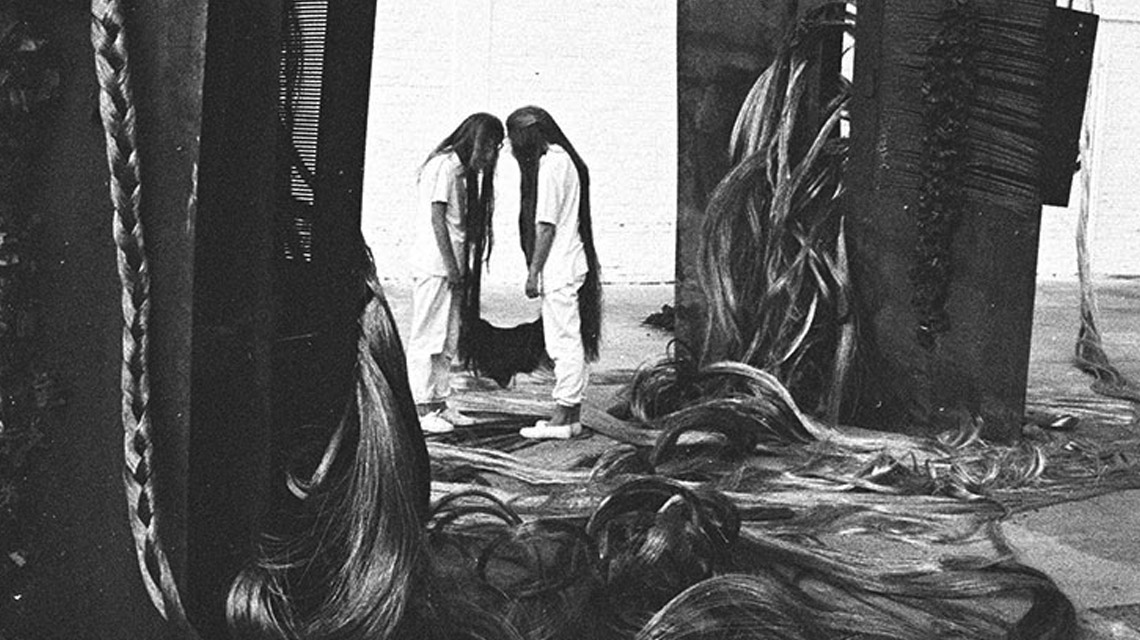

I have the impression that the museum or the gallery is not the real home of Tunga’s sculptures. [1] Nor any site, even outdoor ones, consecrated to the exhibition of art. They seem to come into their own, to take on their true vitality, as part of the literary, photographic, video or performance narratives which Tunga has ingeniously contrived for them (these have almost always involved collaborations with other artists and performers). And this despite the fact that materiality, material presence, material inflection, seems to be Tunga’s essential language.

Perhaps this impression originated in my first experience of Tunga’s work, which was not in a gallery exhibition but in his house in Rio de Janeiro. Estrada do Sorimã 512 lies at the foot of the great rock Pedra de Gávea, smooth, vertiginous, covered in vegetation, radiating heat, a pebble magnified a million times – contradictions of scale, weight, substance, which seemed to be prolonged as one entered the work space shared by sculpture, books, kitchen equipment and a low-slung hammock.

A long tress, enormously heavy made of braided lead wire, clung to the floor. A rude “club”, a conglomerate of lumps of magnetic iron, leaned against a wall. The motif of the tress of hair was taken up in an image painted in delicate brush-strokes on a large piece of fine silk hanging from a string (an image bearing also a distinct resemblance to the force-fields of iron-filings round a magnet). Equally intense, in this first impression, was a feeling of the physical reality and presence of certain materials, and of intellectual bafflement. An individual object – a metal comb holding a mass of coppery wire, for example – captured the attention because it made a startling and unexpected analogy or meeting-point between “sculptural” energies and those of the human body. But none of the objects to be seen, each so distinct in its own material identity, seemed to be related to the others. I had a powerful sense that familiar certainties, that accepted morphological systems of relationship – the plastic, the serial, the generic –, no longer applied, and that these objects were the result of searching for some new order of relationship. But it was not a question of finding a merely intellectual “key”, because of the work’s overwhelming sense of immersion in the physical world, which threw into question the relationship of materiality to meaning.

An “installation” by Tunga is a way of combining the discreetness of objects with a process of their “mutual contagion” (to use his own phrase). A way of combining fixed with fluid identities in the form of a circuit, or continuum, of the flow of energy. In Lezarts (1989), for example, the metals iron, copper and lead are linked both elementally, as if they generated electricity between them, and figuratively in the image of the hair and comb. The combs in some way control the unruly hair/wire as a sluice-gate channels water, or wiring, switches and junction-boxes control electrical currents. The braiding, too, introduces an element of pattern, order or “culture” into the wildness of the hair/electricity. But the pattern of braiding is also analogous to the snake’s skin, a pattern of nature. Similarly, magnetism is here presented in a random, disorderly form very different from its concentration in the carefully-wound coil of the electric motor. All in all, Tunga’s installations heighten tensions between order and chaos, in a way which rebounds on our habitual ways of delineating and naming portions of reality.

An audacious proposal in early modern sculpture was Gabo’s creation of a “virtual volume” by means of a vibrating wire. Its insubstantiality overturned traditional sculptural concepts, but there still had to be the notion of a ‘real’ volume in relation to which the other was seen as “virtual”. Tunga would supersede the dichotomy: “When you plunge into water, the shape you make is real not virtual. When I enter a room an equal quantity of air leaves the space”.[2] How to indicate this reality? An early series of sculpture which Tunga made (Exogenous Axis, 1986) were formed by, so to speak, solidifying the air between two body profiles of a particular person placed face to face (the seven objects in this series were derived from seven women who represent something outstanding in Brazilian society for Tunga). This interval of air materialised as a steel chalice (the head) mounted like a precious receptacle on a bell-like pedestal of turned wood (body). The solid of the sculpture is everything which is not the image of the person but is their presence, paradoxically.

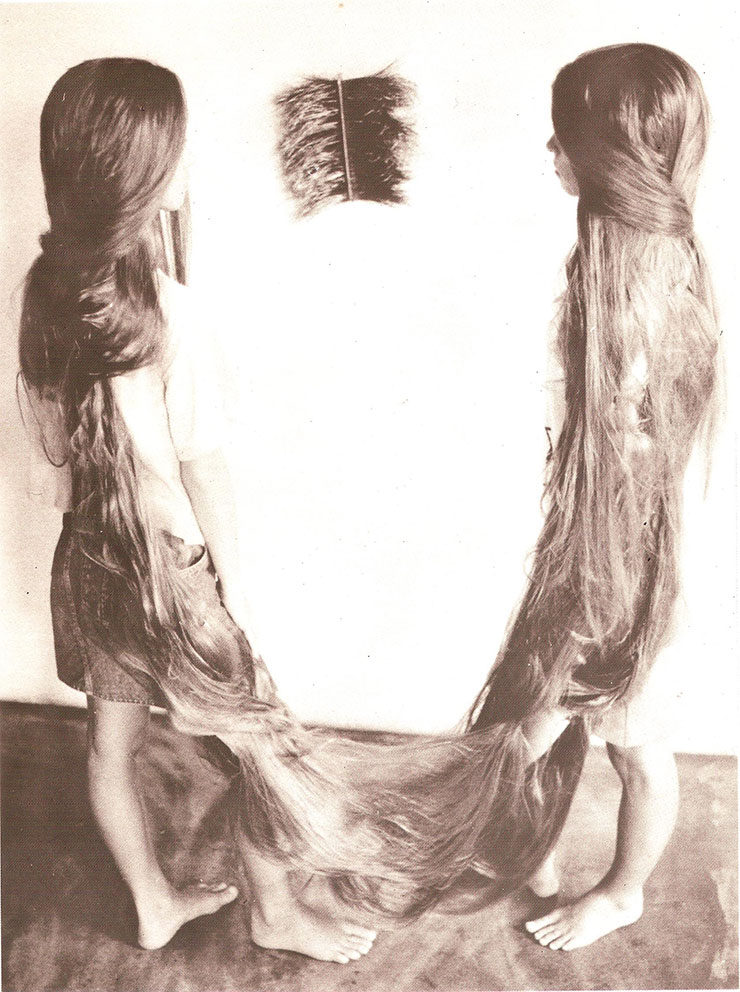

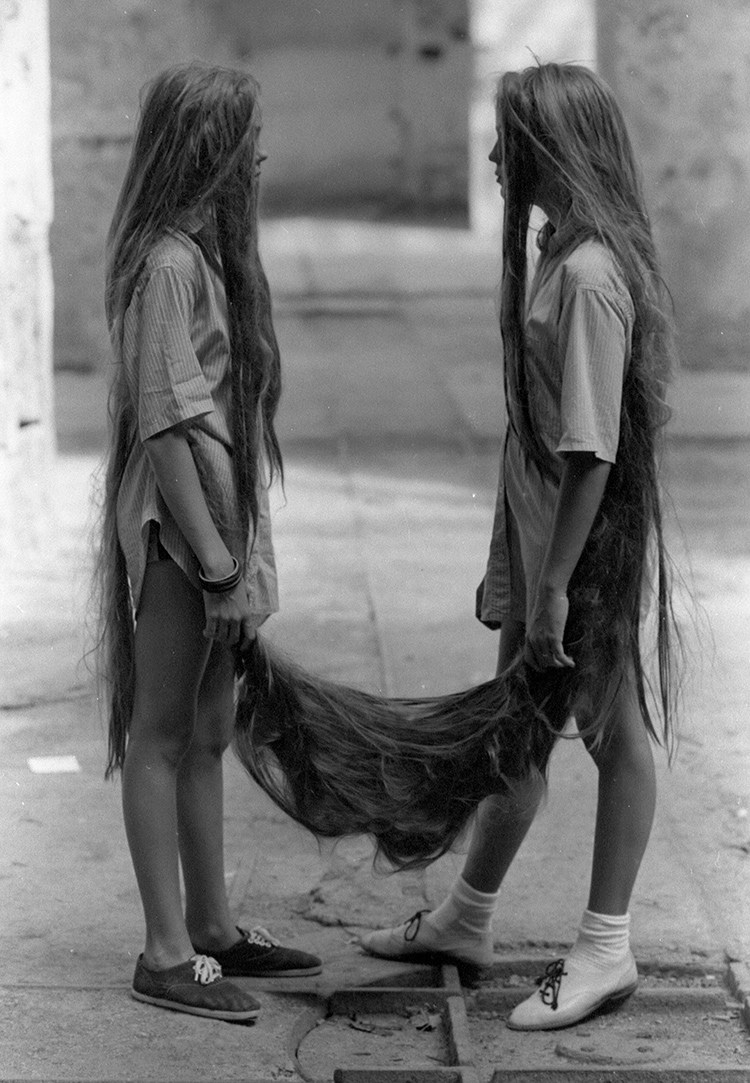

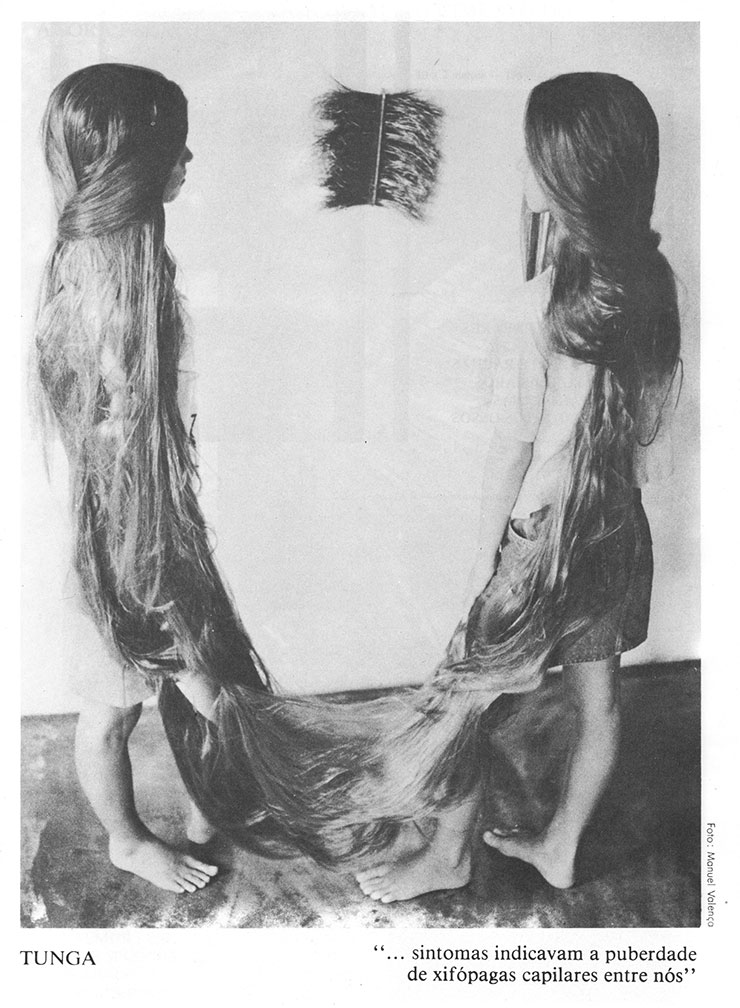

At our first meeting Tunga gave me a small booklet. Purporting to be (perhaps really being) a reprint from Revirão 2 – Revista de Prática Freudiana (Rio de Janeiro, 1985), it spun a fantastical yarn to account for the way Tunga’s objects, though apparently distinct, were linked and echoed in one another. He begins with his own narrative of his (1981) project to make a film while travelling through the long curved tunnel of Dois Irmãos (Two Brothers), just outside Rio on the São Conrado-Gávea road, a film which was then joined to make a loop, a tunnel-without-end, “an imaginary torus(topological ring) in the interior of a mountain”. And he is led on (or sideways) by the discovery of newspaper cuttings and anthropologists’ reports to make weird connections. For example: the ‘hair’ theme originates with a scientist’s report about Siamese twins joined by the hair. After their death the strange trophy of their scalp passes to a woman who extracts two blond hairs from it to embroider an image from her dreams. As she does so the threads turn metallic, apparently to gold. The scalp passes to the Temple of Yun Ka, where the men engage in painting images on silk with gestural brushstrokes while biting their tongues! They were so entranced by the woman’s embroidery that they kept her there in a state of perpetual sleepiness to produce the somnolent images brushstroked on silk. This is the origin of the silk paintings (seda = silk, is the same root as sedative in Portuguese). And so on. There are other far-fetched links. (As I read I began to become uncomfortable with the traditional male/female roles assigned in the story, but then I thought they were perhaps an outgrowth of the archaism of the literary style, and Tunga might say anyway that these male/female traits are aspects of a single self. He likes to cite somnolence and indolence as a feature of his own way of working.)

Why construct this alternative “documentation” which mixes the plausible and implausible, the phantasmagoric and the mundane? Perhaps to mock the accepted raison d’être for artistic production which is given by the museum and the art market milieu, by inventing another “circuit” which crosses the world, time, as well as the anthropological, paleontological, zoological, paranormal and medical spheres (tongue-in-cheek of course, since he reveals that each of these discourses is as bounded as any other). It could be a way of countering the fixation on the autonomous art object by means of a fable where one object or body is immersed in another ad infinitum (in his story he moves from the commonplace to the ultra-precious, and from molar to mountain). In Tunga’s film O nervo de prata (The Silver Nerve), made with the film-maker Artur Omar, this notion is extended by the metaphor of swallowing which occurs throughout the film.

Tunga’s recent book Barroco de lírios [3] (which he edited, wrote and laid out himself), is clearly an attempt to present his work in luxurious photographic detail, while moving it from the dull, flat time and space of gallery and museum shows to a more mysterious and potent dimension. Each sequence of images encapsulating a particular work is accompanied by a text typographically woven into the brilliant montage Tunga is able to produce as he moves along from page to page.

A memorable sequence, (“Ao”), begins with a small circular ring of cine film mounted like a jewel on a silver page. Then follows a loose transparent acetate sheet printed with the X-ray image of a human skull on which a circular void suggests a brain trepanation. But the cloudy brain seen through this cavity turns out, on the next page, to be a smoke ring floating in space. Immediately following are photos of the interior of the Dois Irmãos tunnel, which we plunge through over several pages while the smoke ring lingers in the tunnel’s vault. Suddenly the smoke solidifies, so to speak, into a set of massive oxidised iron rings, bringing us abruptly to the other end of the sensory spectrum in which our earthly bodies live their lives. The iron rings, only the smallest of which, perhaps, one could lift by hand, fit neatly into one another. Parallel with our bodies, our minds contemplate Tunga’s exegesis of an abstract construct: the topological ring (in exhibition contexts, the circular tunnel has been shown via projection of the loop of film and the iron rings shown as sculpture).

Behind all this is felt, throughout Tunga’s work, the formidable matrix of tropical nature. It is all the more powerful for being conjured up tangentially, in fragmentary, old-fashioned, leisurely texts which draw on the mannerisms of science, liturgy, esoteric lore, travellers’ tales, explorers’ adventures, naturalists’ narratives, experimenters’ reports. In this “art” book the ambience of science is the predominant conceit; as far as I could make out the word art, or artist, is used only once in the entire book and that is to describe a certain Cuban cigar-roller, who, following the many images of reciprocity and “mutual contagion” traced in the book, “smoked as he made cigars, and … made cigars as he smoked”.

Perhaps one of the aims, or side-effects, of these stories is to reexamine, or to play with, the notion of narrative in relation to other structures. The narrative element would seem to conflict with the idea of a circuit: narrative appears to lead somewhere, to have a beginning and an end, whereas the circuit is a continuum. Narrative is a thread (“yarn”), like the thread out of the labyrinth, or like the gold thread in embroidery which enriches the surrounding dross. It also connects with the hair-wire in Tunga’s sculpture, which runs in a continuum from chaotic hyperbolic excess to orderly braiding (an “orderliness” which introduces another kind of visual energy). Scientific investigation itself seems to have a borderline with narrative, beginning, following up and analysing clues which lead to some kind of final proof (in Tunga’s stories there are narratives which come through at second or tenth hand, and many things which may or nay not be evidence). In fact Tunga’s stories, as a further complication of the workings of language, play with or against scientific investigation as such, by insisting on describing every object or event in terms of others. Is a non-metaphorical language possible, or is metaphor the sine qua non of language to such an extent that science’s attempt to describe or know an object in “itself”, and not in terms of another, or, correspondingly, the art institution’s attempt to isolate the object from life-experience, is a kind of folly or mania?

The literary elements of Tunga’s presentation do not, in turn, negate a concern with certain ‘sculptural’ questions. Clearly, from one point of view, the legacy of modern art up to now could be seen as attempts to a work out in visual terms a new conception of relationship, change and metamorphosis which goes beyond classical space/time. At first artists struggled directly with that inherited space/time.

The surrealists’ language was built from incongruity of relationships. As everyone knows, one of their inspirational sources was Lautréamont’s phrase about “the chance meeting of an umbrella and a sewing-machine on an operating-table” – essentially a still-life image. And the surrealist “shock” tended to come from the incongruous combination of conventionally-depicted objects (de Chirico, Oppenheim, Magritte, Dalí), hybrid bestiaries (Lam, Ernst), perspectival realism made eerie by the dream (Delvaux, Balthus), and so on. The components of the surrealist object and even the Duchampian Ready Made needed to keep their unitary, everyday identity for the change of context, or as Duchamp said, the “new thought for the object”, to take effect. The concept of relationship and morphology underlying what is broadly known as abstract art seems to be based on another model: natural or organic structures as revealed by the physical sciences, for example, plant growth, crystalline or cellular structures. Biomorphism (Miró, Calder, Arp, Schwitters) occupies some sort of middle-ground between abstraction-concretism and surrealism. Other artists came to one or more structuring elements, rather personal to them, which would allow serial development: plus-minus and asymmetrical horizontal-vertical equilibrium (Mondrian), arabesque (Matisse), pictographs and notation-systems (Klee, in whose work they are combined with plant-growth, crystalline formations, etc), gravity-less geometry (Malevich, Lissitsky), force-fields (Moholy-Nagy, Vantongerloo), and others. These structural elements, the remnants of classical space, were increasingly kineticised.

What is so striking about these forms of production is each one’s characteristic of a species or genus. Matisse said: “No two leaves of the fig-tree are exactly the same, but they all proclaim ‘Fig-Tree’!” The art work proclaims this inner logic or authenticity which is also a proclamation of the artist’s identity. But, paradoxically, because of another logic, that of the art market and its institutions, this organic metaphor of production and identity became a mechanical one: of the production of a type of commodity which is highly individual and instantly recognisable. Some artists’ work implicitly recognises this change and plays upon it (such as Andy Warhol’s). But new strategies are also being proposed, which can be located as much in a Brazilian as an “international” history. Tunga’s search for a new order of relationship, a continuum where one body or discourse is immersed in another, is one of these strategies, of which experiments in the relationship between physical object and verbal text is an essential part.

“Thought and language are inherently systematic and fixative, while nature is inherently elusive and protean.” [4]Tunga appears to position himself to throw into question whether such a dichotomy is simply either true or false. And in doing so he illuminates, I feel, a fascinating and abiding problematic of Brazilian art. The duel between conceptual ordering and prolific nature, between cerebral schema and biological pulse, runs in many guises through the work of Brazilian artists and thinkers in the 20th century. It can be found in Oswald de Andrade’s writings during the first explosion of Brazilian experimentality in the 1920s, when he said that in Brazil “We have a dual heritage: the jungle and the school”, [5] and in Sérgio Camargo’s white reliefs of the 1960s, a precise, condensed, refined interfluidity of order and chaos. Paradox and irony only add to this richness of opposites: for example, one could compare the way the “body” is present in Waltércio Caldas’s apparently disembodied and cerebral contemporary work with the way the “mind” is illuminated in Lygia Clark’s “language of the body”. The notion of vivências – a word intended to reverberate with the sense of immersion in the world, lived experience, the fusion of sensory and thinking processes – was a favourite of Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica. They often used it as a check for gauging the efficacy of a proposal in the face of the alienations of intellectual academia, commercial consumption and the institution of art. Thus Oiticica could sometimes execute the elegant reversal of his own premises in order to sustain the living thought in the material from being reduced to an inert object. He could apparently empty his work deliberately of the sensuous delectation for which it first became celebrated (for example in his early Bolides, Nuclei and Parangolé), and introduce the notion of the “supra-sensorial”, a skeletal, almost indentityless structure, a framework for the spectator’s own imagination to inhabit, a response which was invited without coercion, without goal. It was not the object which was important but the way it was “lived” by the spectator/participant. His descriptions of his own works treated them rather as if they were verbs, not nouns.

Oiticica produced a remarkable and rather little-known object near the end of his life, the Ready Constructible (1978), which was accompanied by a verbal text in the form of notes. He invoked Duchamp in his title only to show how far he felt he had moved from the Frenchman. This unprepossessing object, this cube of hollow mass-produced bricks and cavities, was Oiticica’s “most extreme exercise” in the interpenetration of, or “fine line” between, opposites in a universalist sense: between the non-determined and the precisely-structured, between “brutalism” and “mathematics”, between the ready and the unfinished, between inside and outside, open and closed, between the earth and every human construction:

an exercise in the concretion of the not-concluded

or

the proposal of determined structures in the exercise of the indeterminate. [6]

Despite the very different sensibilities – and the different generations – of Oiticica and Tunga, the meaning given to the material object by Oiticica’s notes about it makes one think again about the imaginative element represented by Tunga’s texts in relation to his sculptures. Tunga’s stories “romance” his sculptures. And yet, since these texts have such a strong element of the literary conceit, tall story, artifice or play, we have no need to solemnly accept them in an earnest spirit of information or pedagogy. They are further scraps of material, and we are therefore redirected again to the material-linguistic transformations, and their closeness to an organic core, which is where I believe Tunga really wants our attention to fall.

Notes

1. Parts of this essay were originally published in Tunga: 1977-1997. New York: Bard College, Center for Curatorial Studies, Sep.-Nov. 1997.

2. Statements by Tunga. Notes taken by the author during a discussion with students at Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, in December 1986.

3. TUNGA. Barroco de lírios. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 1997.

4. MUECKE, D. C. Irony and the Ironic. London: Methuen, 1977.

5. ANDRADE, O. de. Pau-Brasil Poetry Manifesto (1924). In: ADES, D. et al. Art in Latin America: the Modern Period. London: Yale University Press, 1989.

6. OITICICA, H. Notes on the Ready Constructible (1978). In: Hélio Oiticica (exhibition’s catalog). Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 1992.