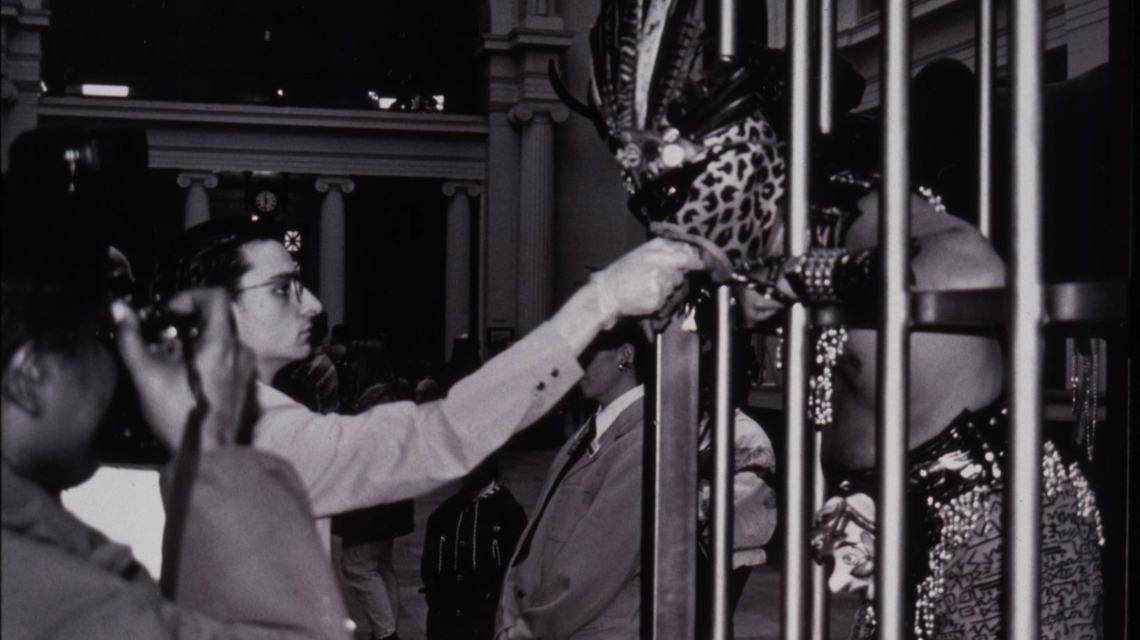

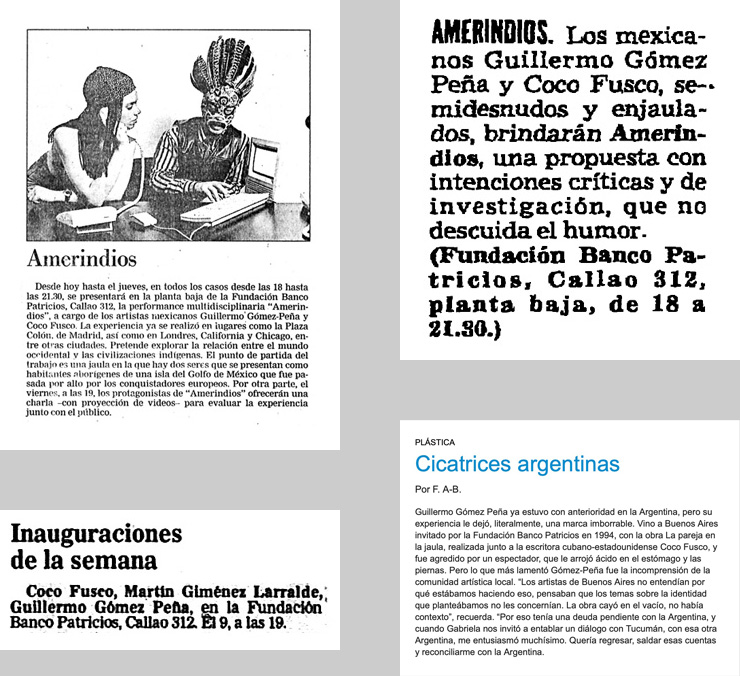

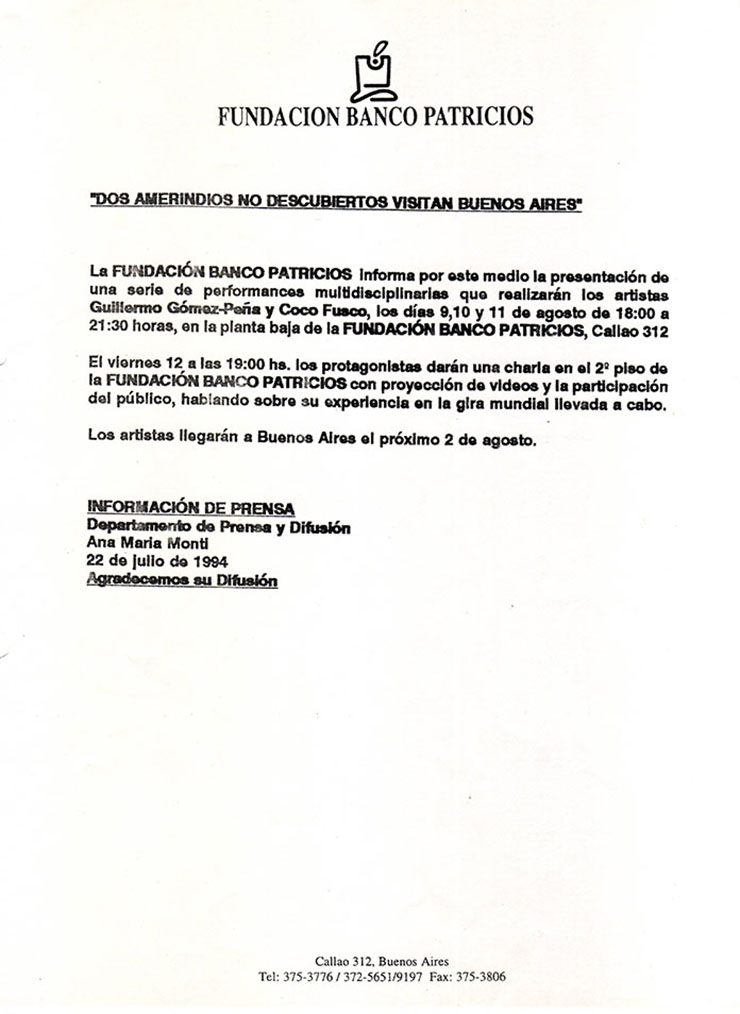

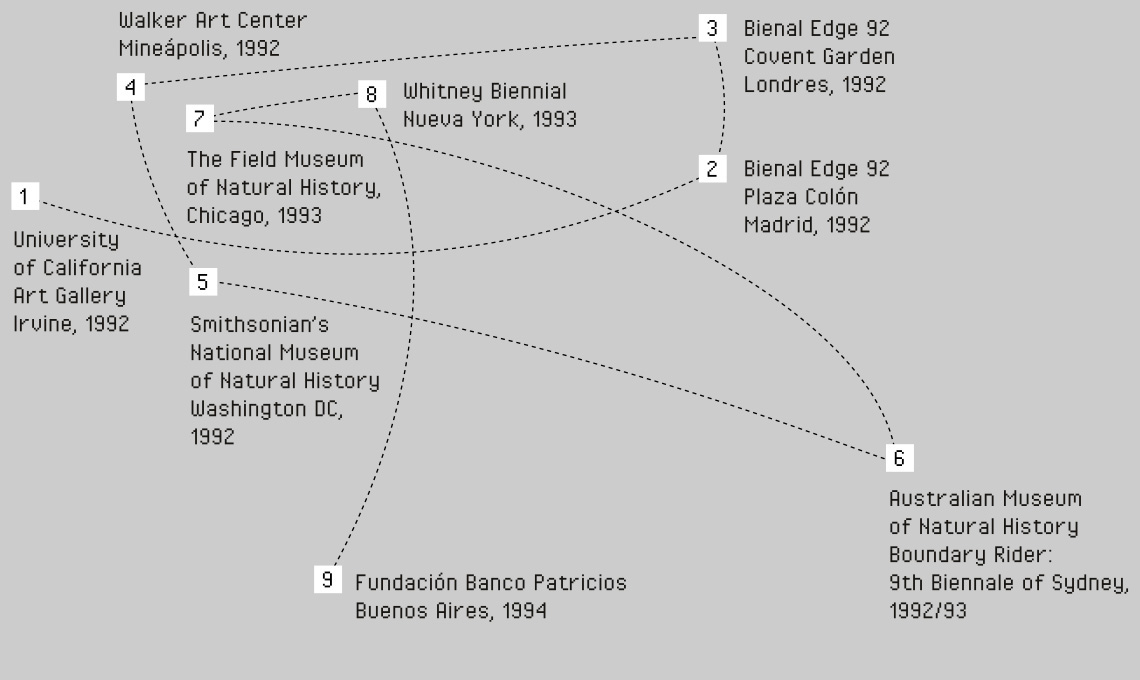

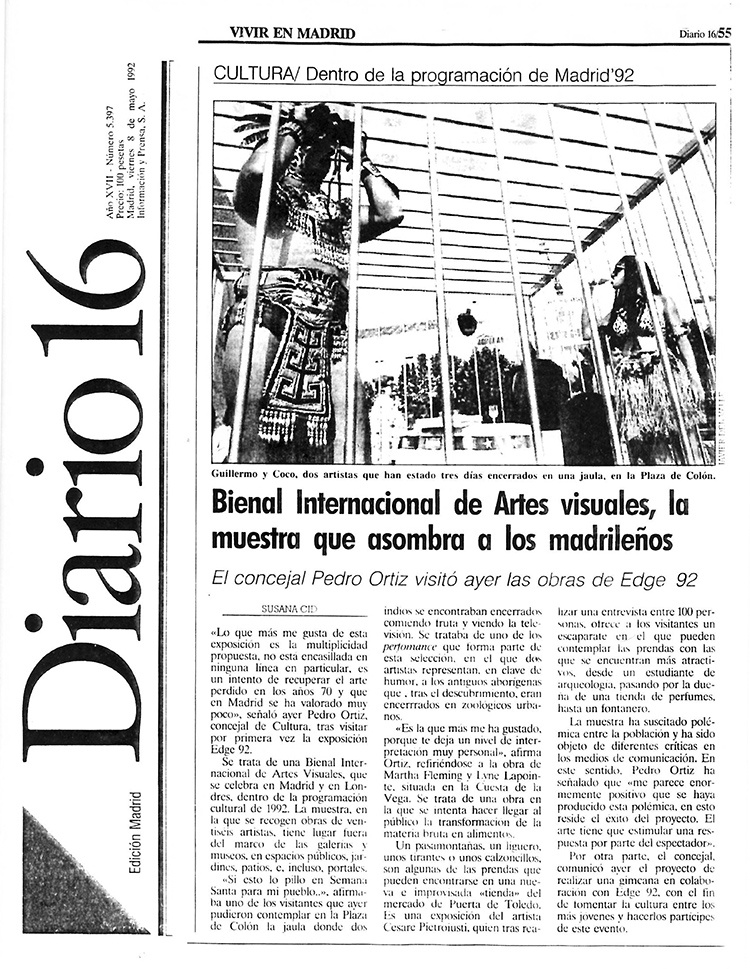

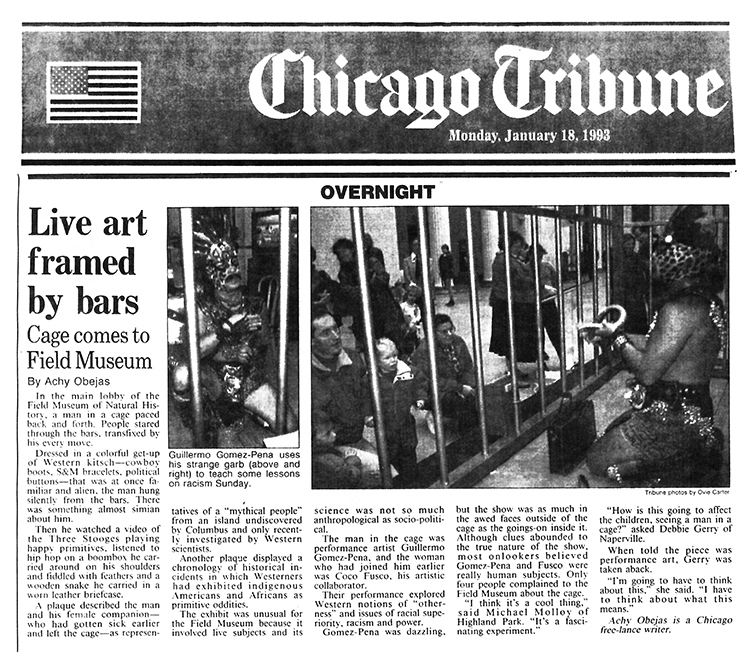

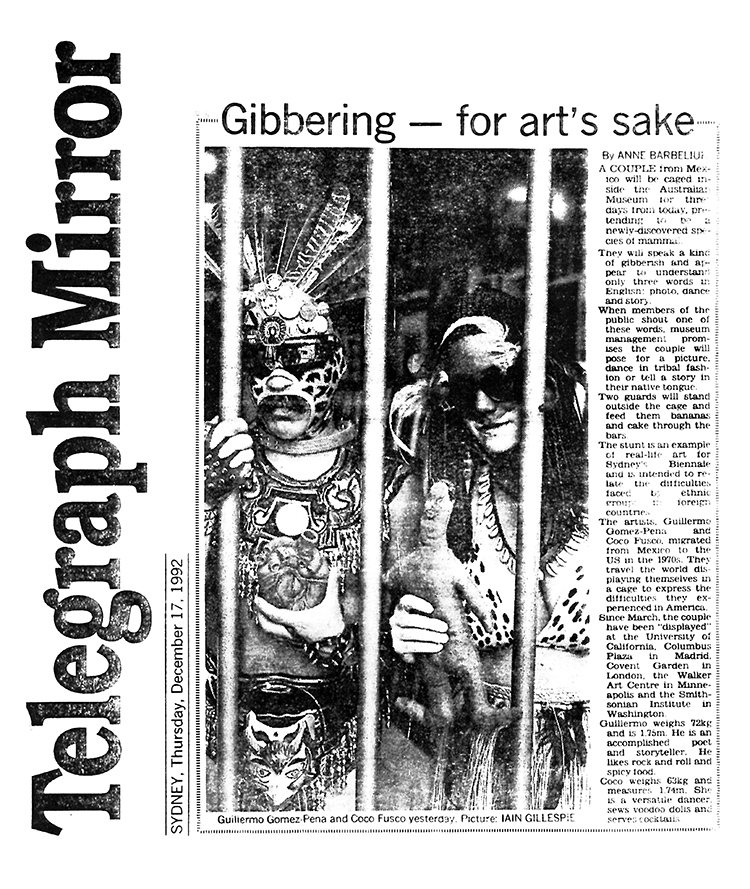

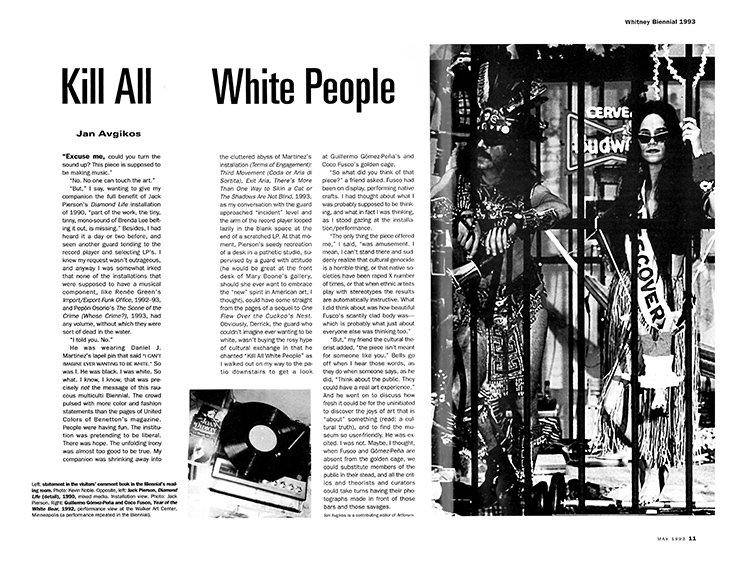

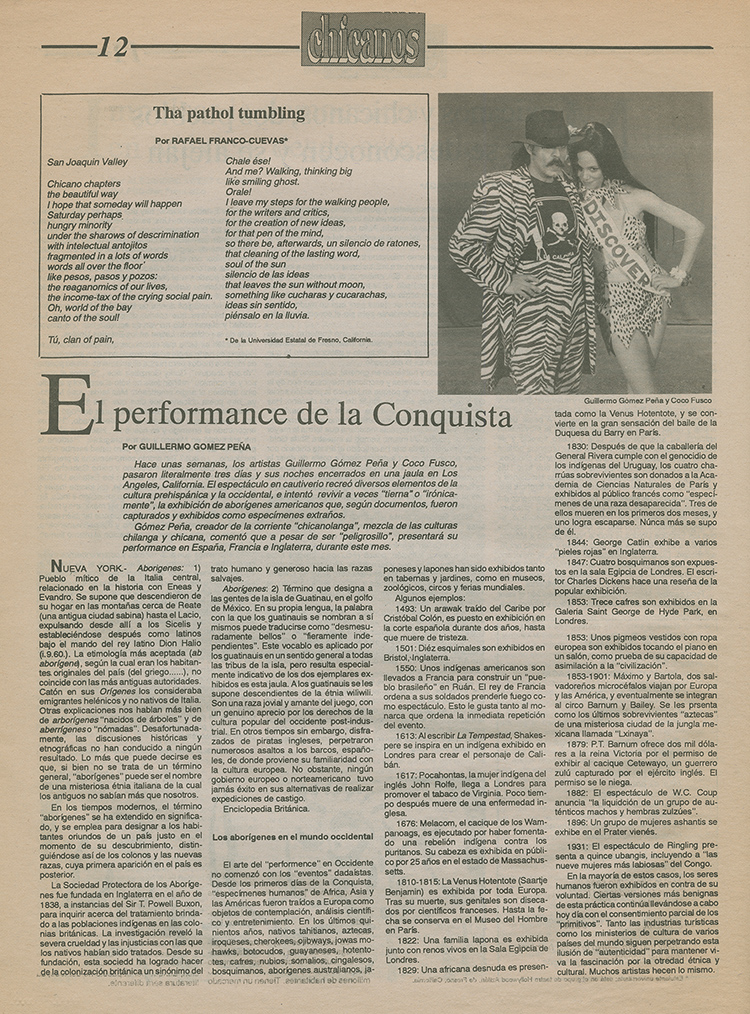

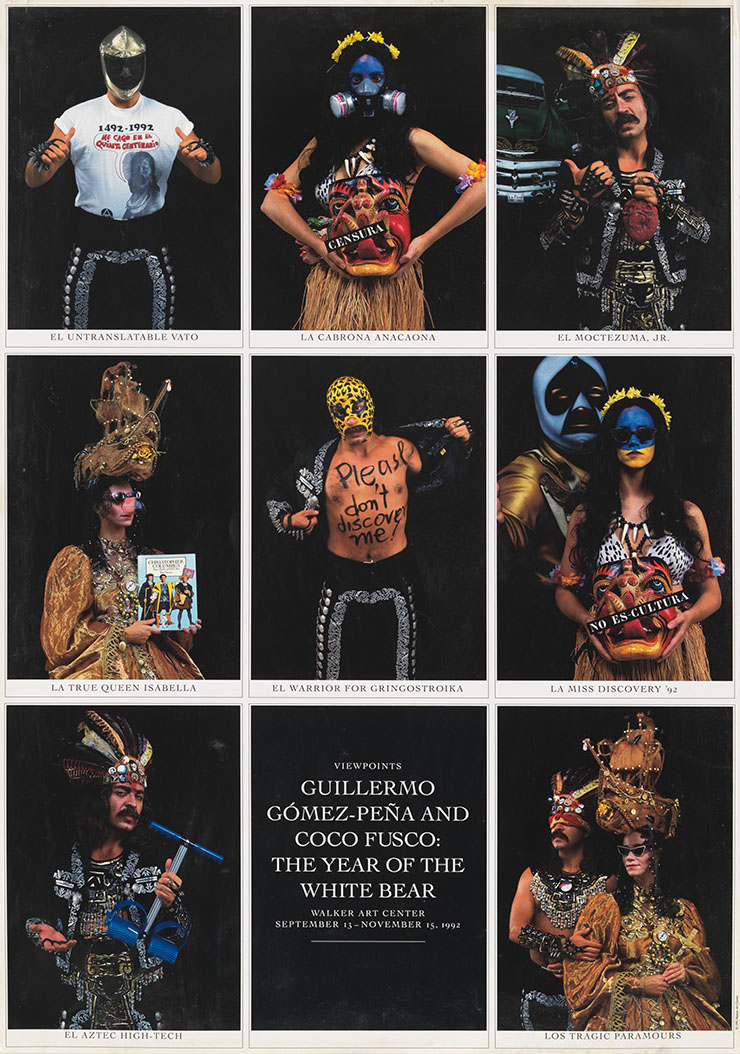

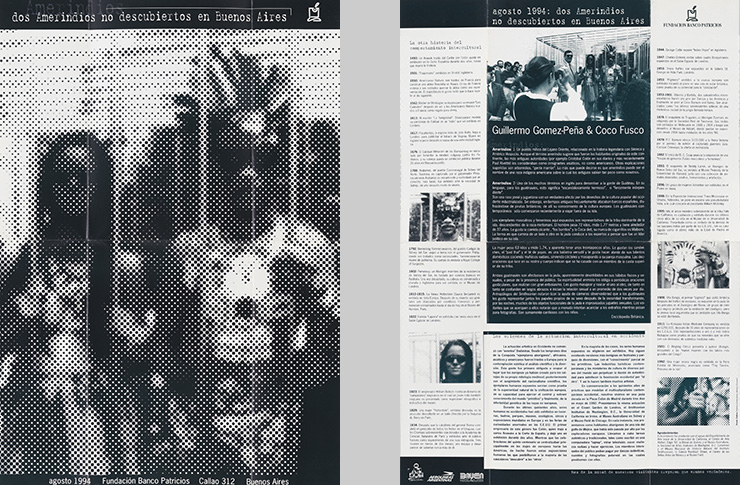

In 1992, artists Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña staged Dos amerindios no descubiertos en Occidente (Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West). The performance’s explicit framework was cultural stereotypes. The authors’ aim was to jar the celebrations of the five hundredth anniversary of the “discovery” of America and to question the oversimplifications of the multicultural museological model championed in North America at the time. The performance consisted of the staged interactions of the Fusco–Gómez-Peña duo, dressed as Indians from a remote and immaculate island in the Gulf of Mexico. Enclosed in a golden cage, they had been torn away from the fictitious human group and culture to which they belonged for display at different institutions in the United States and Europe, the regions the piece visited. The presentation in Buenos Aires in August 1994 was the last stop on the performance’s tour and the only one in Latin America—in a manner of speaking, since the United States cannot be considered in isolation from Latin America: by the nineteen-nineties, major demographic changes had altered the United States’ foundational myth. I am speaking of new cultural variables due to a growing Spanish-speaking population and African-American community that, after Vietnam and the cultural wars, radically transformed contemporary culture and drove a hemisphere-wide civil rights agenda. Indeed, Coco Fusco asserted that the performance was conceived for a Caucasian audience used to “festishizing representations of Otherness.” [1]

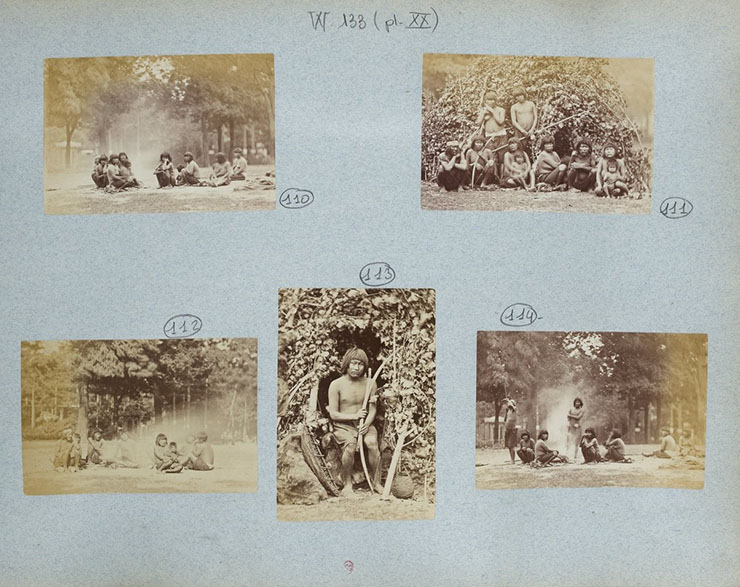

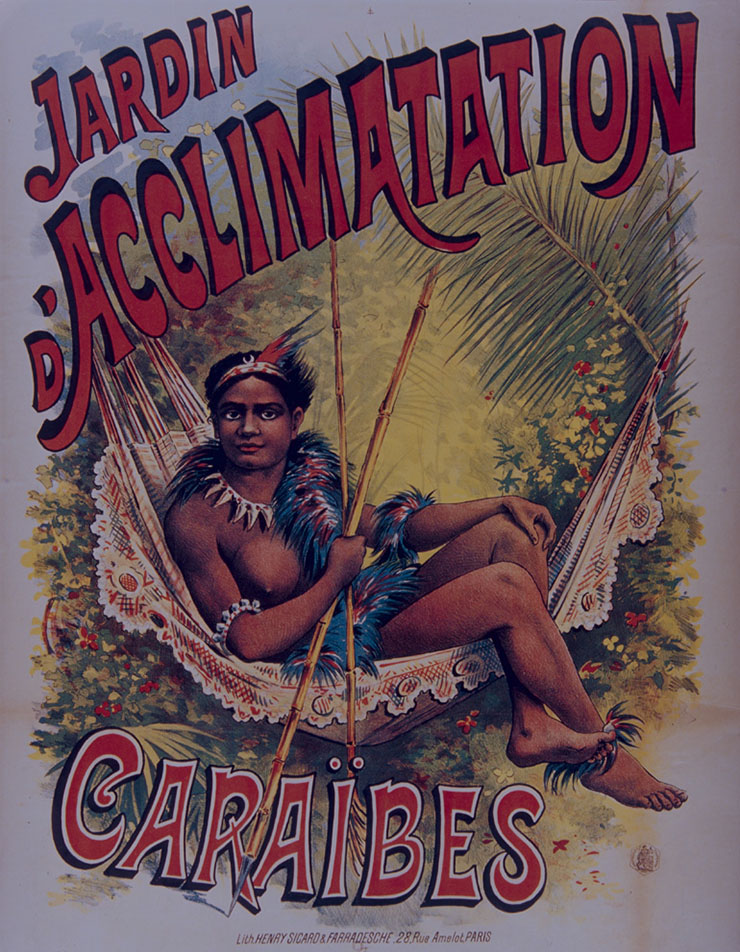

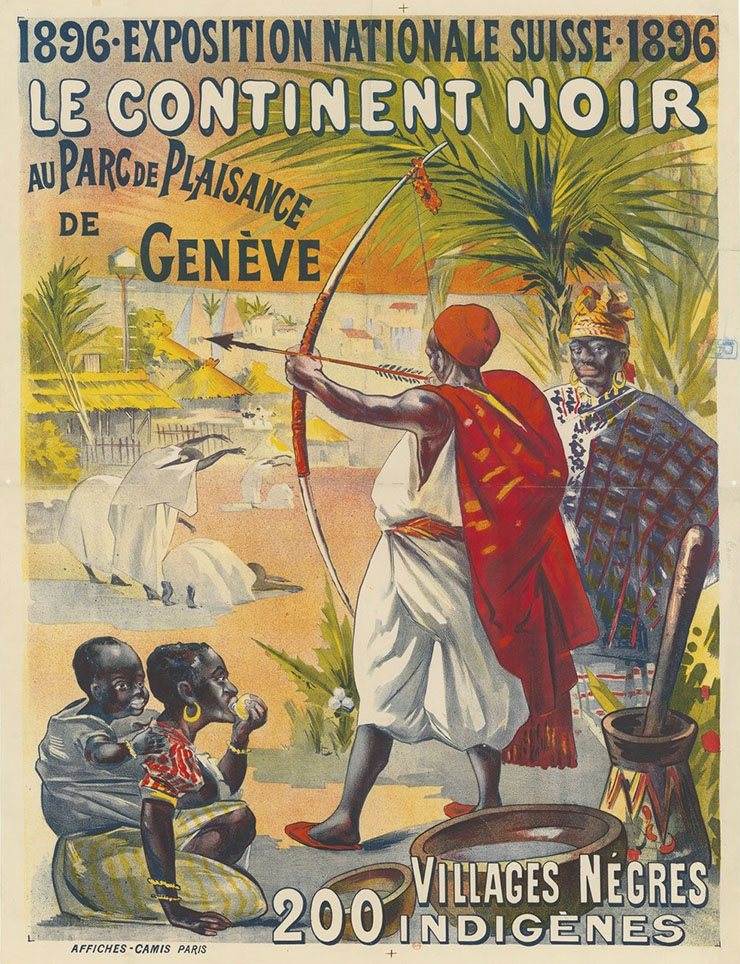

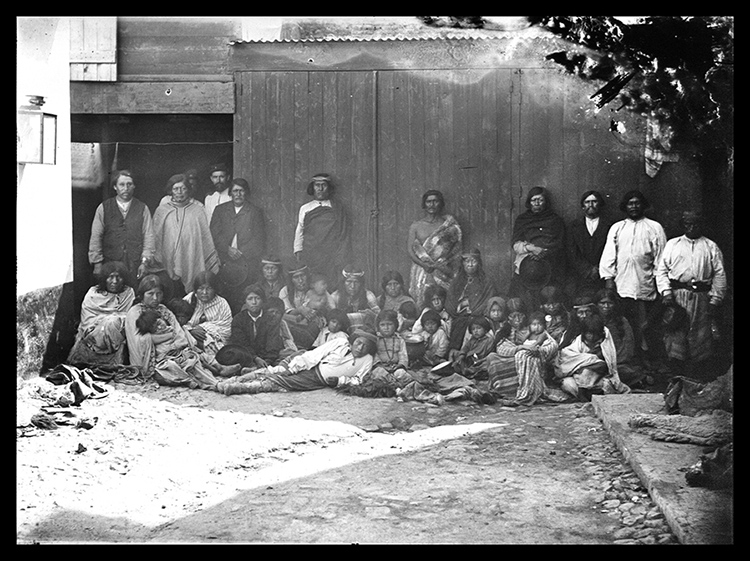

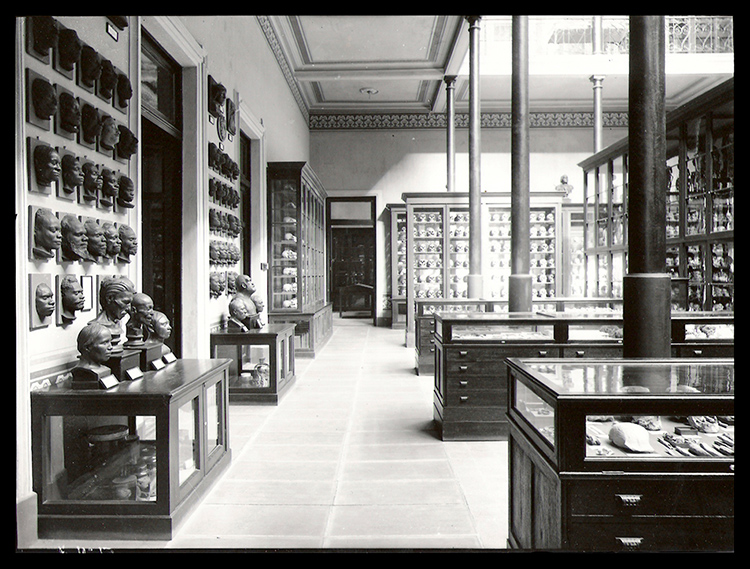

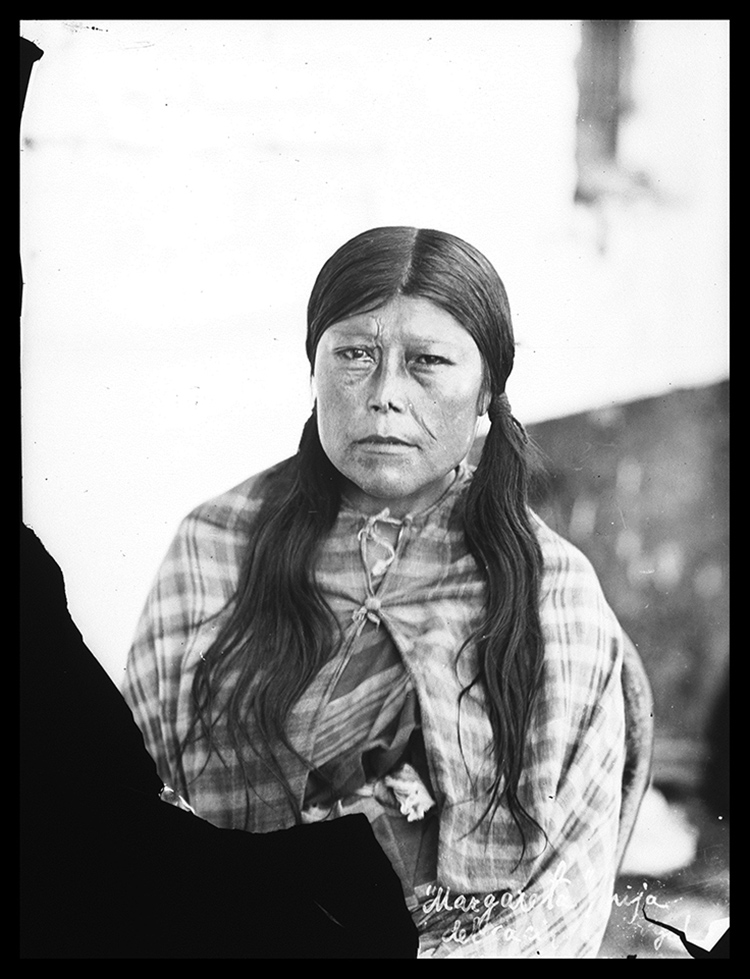

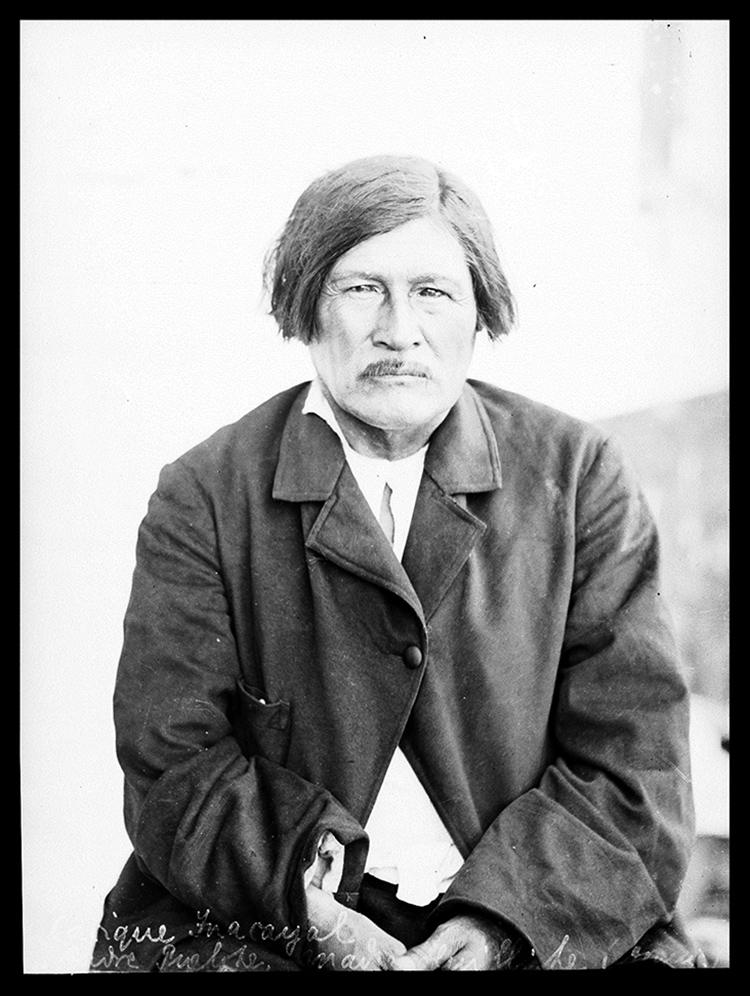

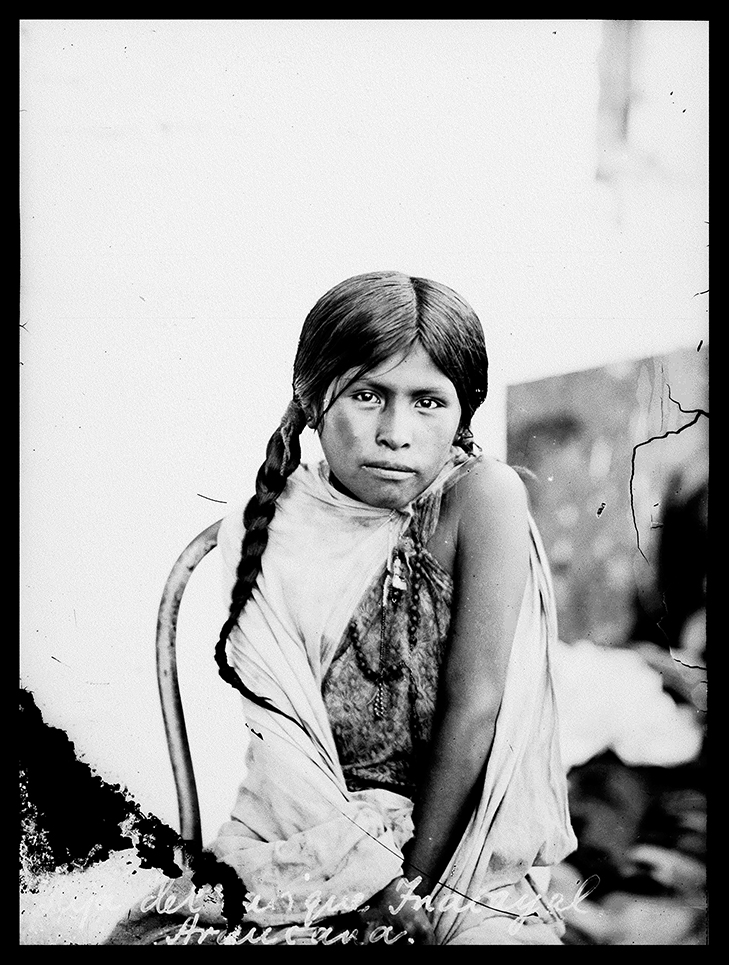

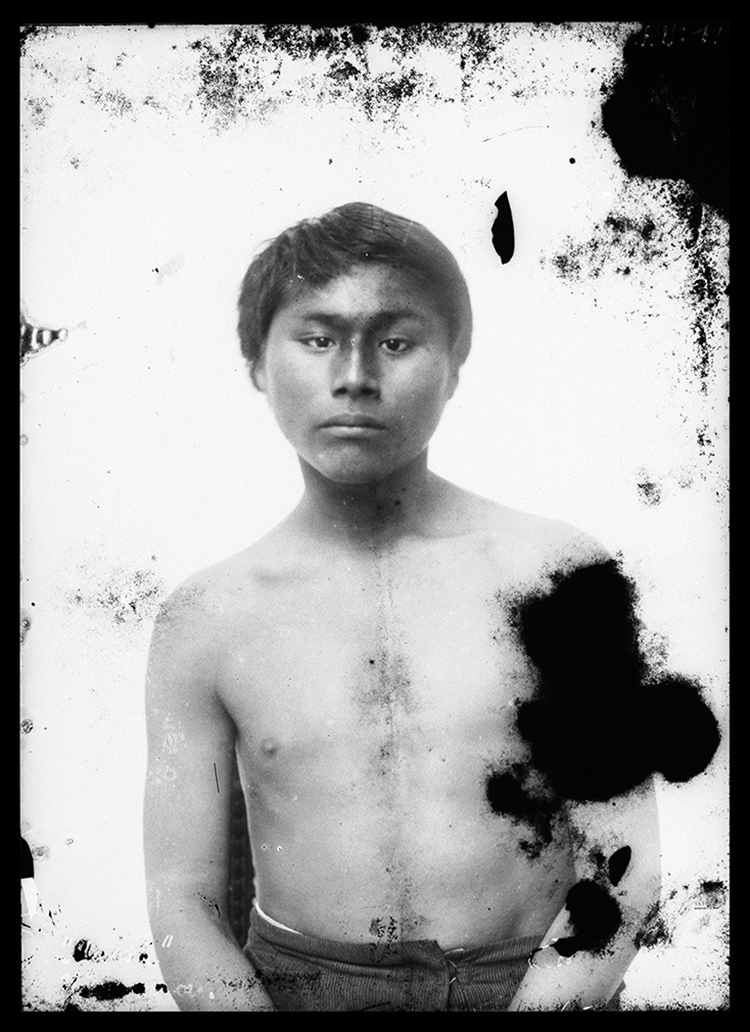

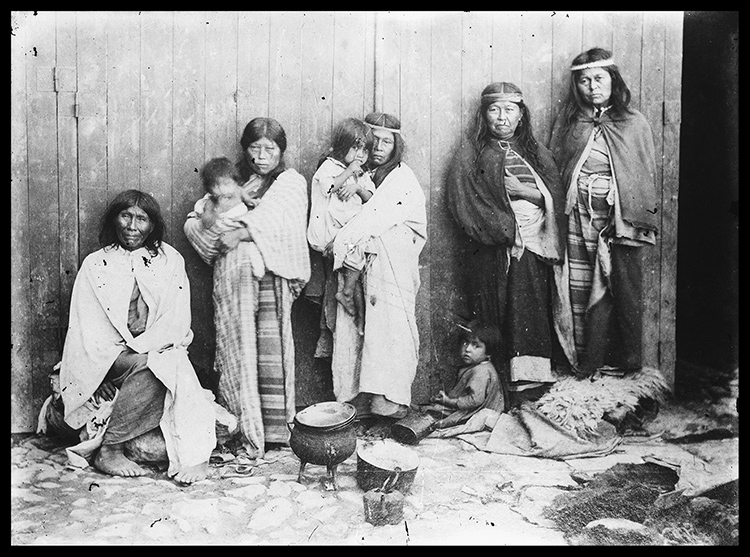

Performers Fusco and Gómez-Peña made use of an unlikely but corrosive fable, a sort of flipside of the fables used in the primitivist textual production of the historical avant-gardes (figures like Tristan Tzara, Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, and Fernand Léger). A satire produced in the dying days of what Eric Hobsbawm called the short century, Dos amerindios no descubiertos en Occidente followed the lost path of the human exhibitions that began to take place in royal courts, fairs, and museums after Christopher Columbus’s arrival in America, exhibitions that reached their height in the nineteenth century. Presented in an array of contexts, the performance also appealed to the persistence in the collective memory of a robust—indeed, indestructible—colonial imaginary grounded in the chronicles and fantastic cartographies of European travelers and illustrators who circulated in the Americas starting with Conquest. Though it was global in breadth from the fifteenth century onwards, that imaginary, with only a few exceptions, was never rigorous enough for science or historical debate. It was, rather, trapped in the terrain of fantasy and of ethnography at the service of an ideology of domination. Fusco pointed out that, regardless of location, that widespread representation had become reality for much of the public. Indeed, both she and her co-author were met by threats and sexual advances. [2]

The artists touched a nerve. They exposed the nightmares of reason held in nostalgia for a dominant culture when that culture occupies the place of another, supposedly weak culture without providing any possible equivalence or encounter with that Other culture—or, for that matter, the Other itself—that might poetically heighten the One’s imaginary. Before decolonial thought was formulated in the Caribbean, Victor Segalen, a French naval doctor in the East, doggedly explored the Other’s constituent aesthetic not as imperative of moral correction but as expansion of the world and heightened experience of the unknown. [3] Segalen’s Essay on Exoticism and his ethnographic novel Les Immémoriaux nourished Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation, a text that, read today without revisionist spirit, re-signifies and explodes the dimensions of Pierre Menard as author the Quixote and of Jean Rhys as author of Jane Eyre. [4]

Dos amerindios no descubiertos en Occidente re-wrote a genealogy of the medium that Fusco called “intercultural performance,” a medium that, according to the specialists, began with the Dada Cabaret Voltaire. The crux of this piece was situating the history of performance in the wake of the colonial undertaking constructed in the bloody representation of otherness. Everywhere it was presented, the piece included a time line of cases of human representation as far back as 1493, when Columbus returned to the Spanish court with members of Arawak communities. Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s strategy was to cannibalize the European avant-garde with the language of its own suprareality without scorning mass culture, spurious ally of processes of hybridization in the peripheries, as Jesús Martín-Barbero and Néstor García Canclini so resoundingly showed.

Salvaging Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s “cage”—as it was known in the nineties—positions the past as a deferred present that today’s archive puts before us as so many unpaid debts. This performance that, according to witnesses, went by unnoticed and without much ado in Buenos Aires demonstrates multiple perspectives that update, cancel, or put off the validity of the colonial imaginary when crossed with identities both national and individual.

Notas

1. The Other History of Intercultural Performance was written in English and first published in The Drama Review in 1994. See Coco Fusco, La otra historia del performance intercultural, in D. Taylor / M. Ramos (eds.), Estudios avanzados de performance, Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2011, pp.311-342.

2. According to Guillermo Gómez-Peña, acid was thrown at his abdomen and legs during the performance. See Archive, review in Página 12 newspaper.

3. Victor Segalen, Voyages au pays du réel, oeuvres littéraires. Paris, Biblioteque Complexe, 1995. (Edition presentée et anotée par Michel Le Bris).

4. Édouard Glissant, Poética de la Relación. Buenos Aires, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Editorial, 2017. (English title: Poetics of Relation)