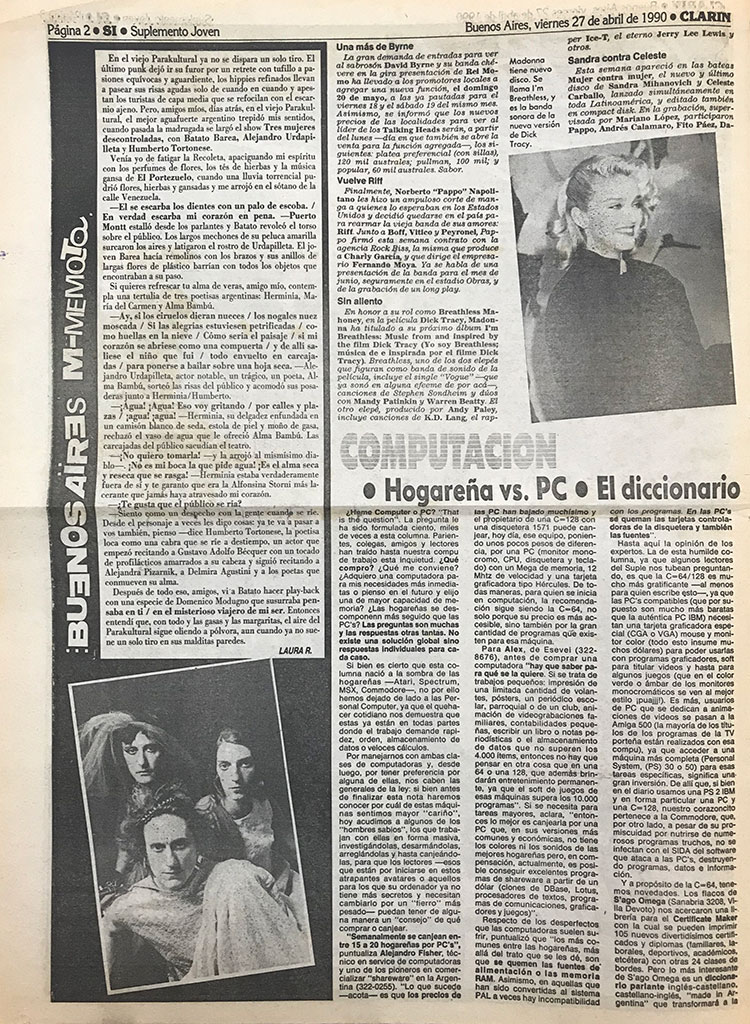

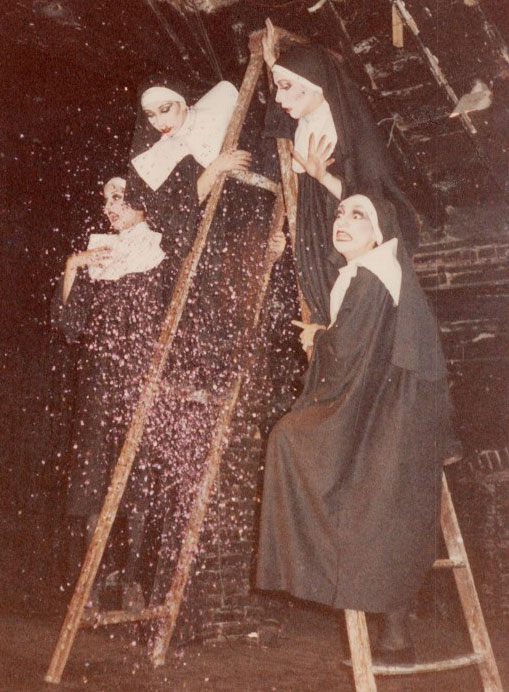

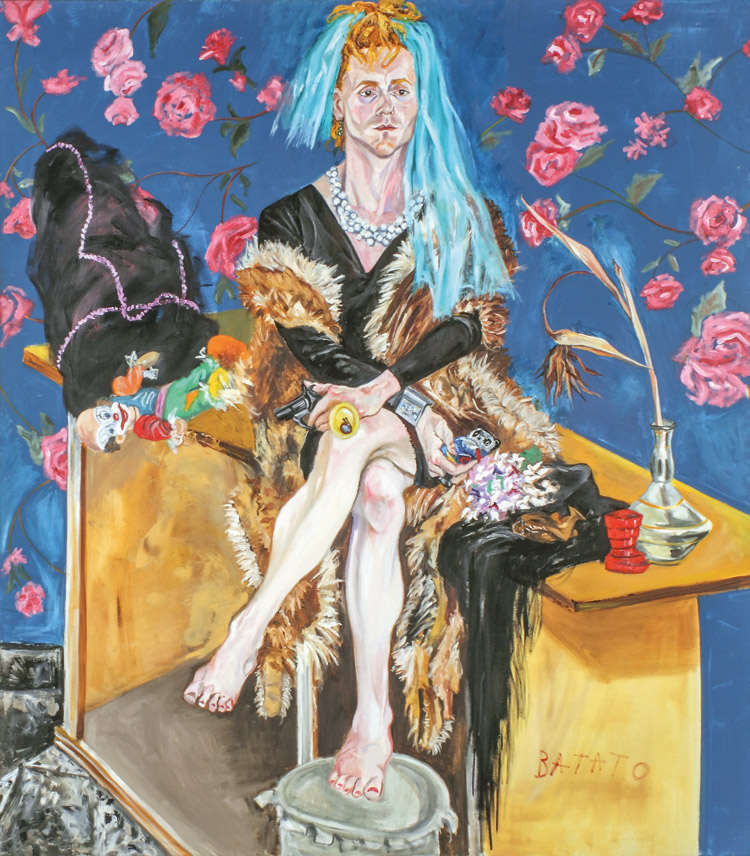

At around two in the morning on June 24, 1990, Batato Barea comes out of the dressing rooms in the back of the makeshift theater in the flooded basement of the Centro Parakultural on Venezuela Street in Buenos Aires, elbowing his way through a crowded audience—mostly punk youth that is shouting, shaking chains, and drinking wine out of carton containers. When they recognize the clown-literary-transvestite-man, they embrace or rebuke him, make way for him or block his passage.[1] The sound of a shot fired interrupts María Callas’s version of the Suicidio aria from Amilcare Ponchielli’s opera La Gioconda. A few minutes of struggle ensue: people running; the basement door by the stage, its back to the audience, opens. Two young men are thrown out. It is raining. The music comes back on. Batato is wearing two wigs—backward to make the blond locks hang down lower over his face—held in place, one on top of the other, by a fuchsia headband; a purple satin blouse; three long plastic bead necklaces; a see-through skirt; heels; and button rings that—like the rest of the wardrobe—he made himself. He is holding a pale-blue silk scarf that he waves with his hand every so often. Dodging the buckets that catch the water from the leaks and the wires that cross the wet floor, Batato climbs the stairs onto the stage.

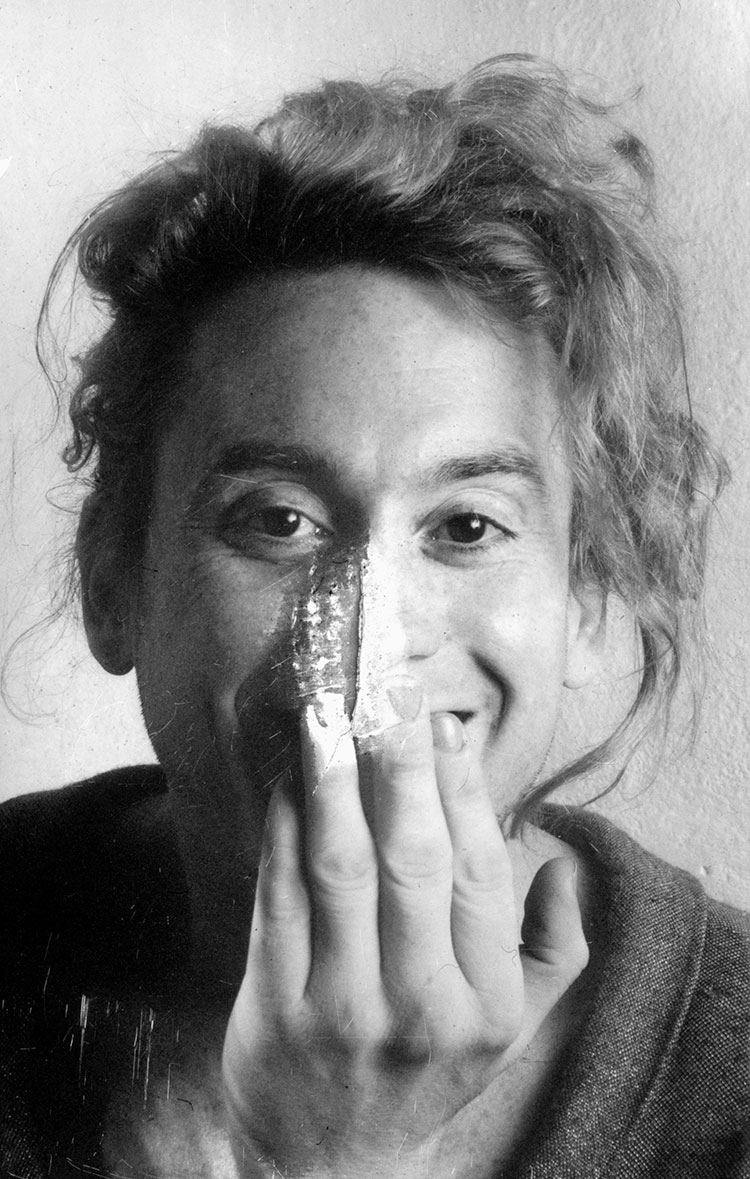

From a speaker comes the deep monotone voice of Radio Nacional announcer Emilio Stevanovich reciting the poem Voracidad del sonido by María del Carmen Suárez, an unknown poet—alive at the time—whom Batato had discovered and recorded a few nights earlier with his small cassette recorder. Possessed, Batato interprets the poems with circular motions, bending at the waist, his torso spinning until he is breathless. “I feel, I feel too much for my body to express,” the amateur poet seems to say.

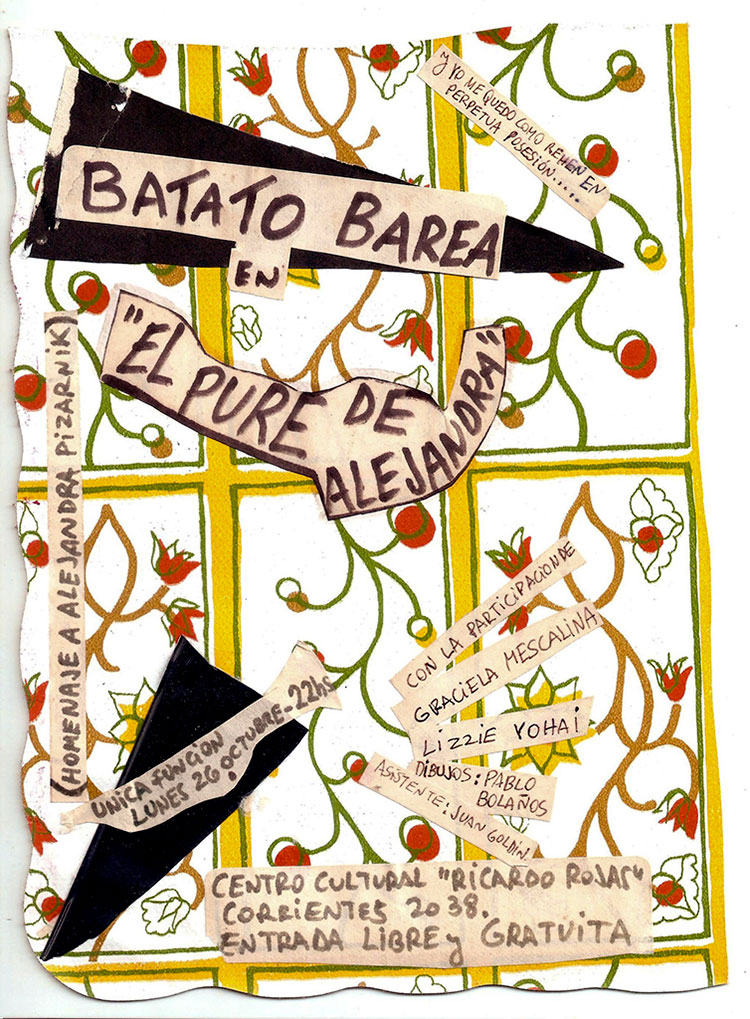

Batato is not an actor, but a clown: in each performance he plays a new version of himself. The set is his body, an erotic and political body, the body of art. With his contortions, laughter, and disarray, Batato interprets the emptiness of existence, metaphysical horror. His is not playing horror, he is in its grips; horror inhabits him, it makes him speak. When he shouts out a Borges poem, Batato names the unnamable, puts his rhetorical energy at the service of the inexpressible. “It never leaves me. Always at my side,/that shadow of a melancholy man.” The audience laughs, and that offkilterness, that false angle, is symbolically subversive: his performance maddens as everything he does maddens, the maddeningness that is his whole life: his art.

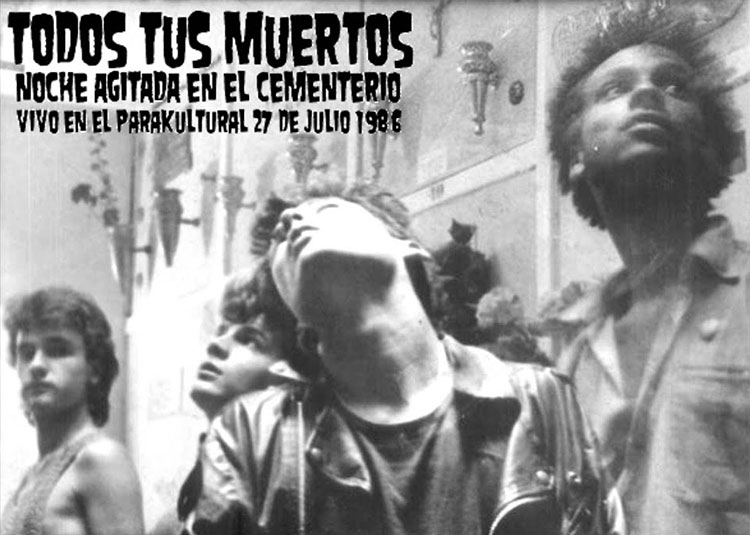

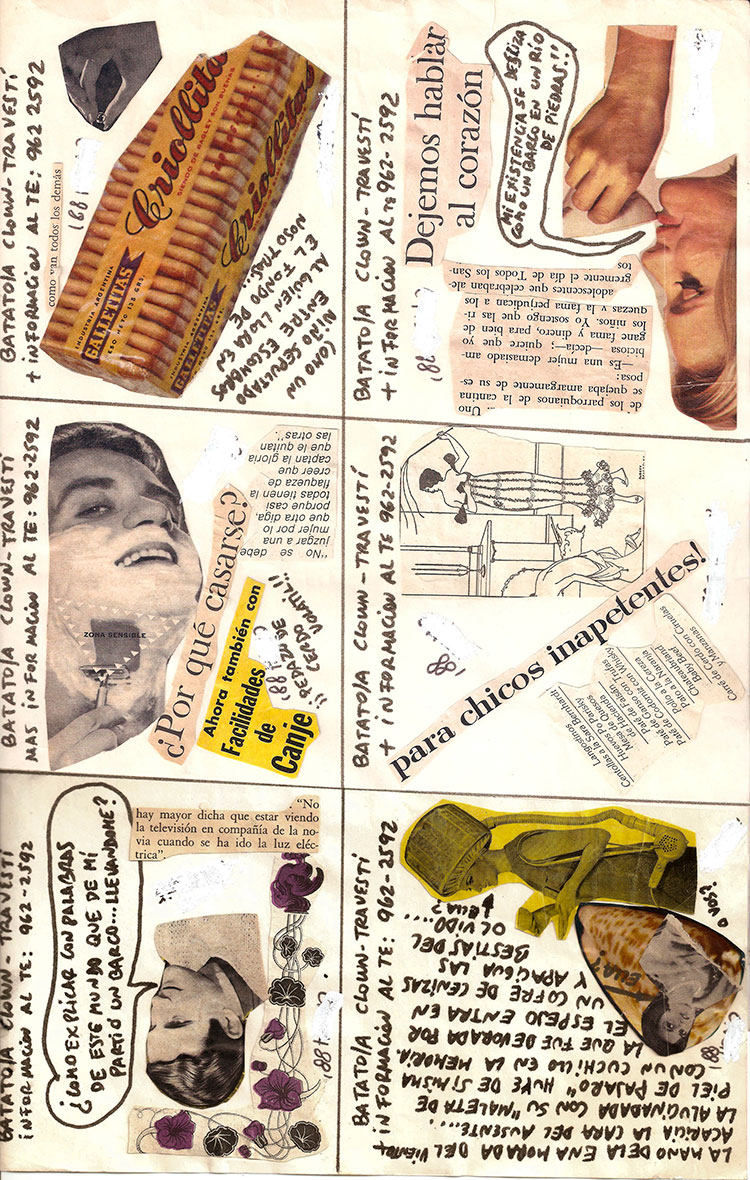

When, after that show on June 24, Batato takes the bus to the Abasto neighborhood—neighborhood of tango, the very heart of heteronormativity in its most extreme form—to work the street, he makes his conversion into taxi boy a work of art. And the essence of that artwork is the same as the essence of the number he did at the Parakultural, surrounded by an audience of punk bands like Conmoción Cerebral, Ataque 77, and Todos Tus Muertos. Batato embraces the abjection of the streets of the Abasto and turns it into maximum virtue. Stepping on the stage with him are his nighttime incursions and transgender prostitution. He is smuggling in a theory of the annihilation of bourgeois logic, its gestures and conventions. He makes the abhorrent noble, daring a spurious and inexorable sanctification. The operation he performs upsets the order of words and things, and the Parakultural audience knows that—or, if it doesn’t know it, it senses it.

Consciously or not—or, rather, not self-consciously—Batato, by considering art life and artwork his body, constructs himself as a romantic hero, like Lord Byron in Missolonghi when he offers his life for the cause of the Greek revolutionaries or, from the point of view of abjection, Jean Genet when he sells his body in El Raval (back then the “China Town”) in Barcelona.

In fall of 1991, less than a year after that performance at the Parakultural, Batato has a transgender friend and fellow prostitute inject motor oil into his chest. As the days go by, the oil seeps through his body until just a trace is left at the original injection site, like those pigments that keep acting on oil paint as time goes by. And it is at that instant when it seems as if the transformation has failed that it takes on meaning: that displacement, that dripping oil, is how Batato, in his art, engages the precariousness that besets a class and a gender. The erotic-political intervention he inflicts on himself carries strains of class struggle and utopia. Brutally distinct from the aesthetic of documentation, his action of grief or protest transforms the transvestite signifier with startling clarity.

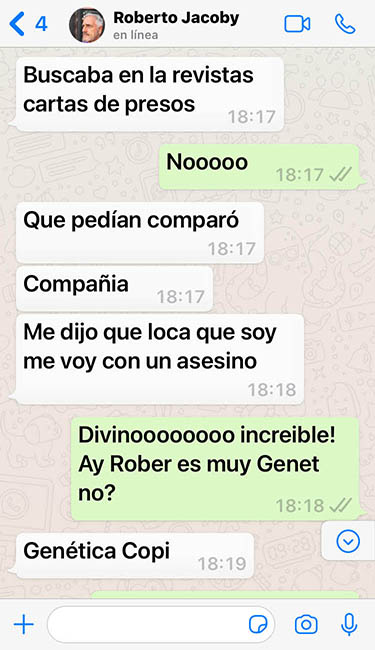

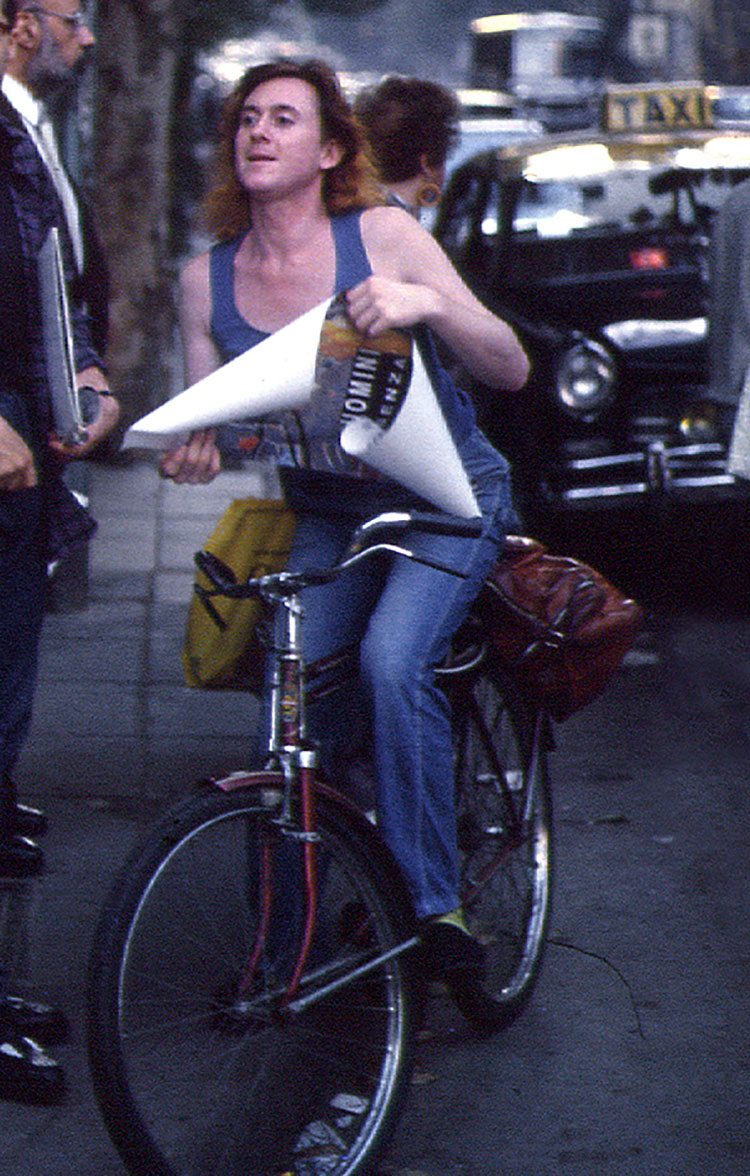

For the past six years—if not more—he has carried in his blood a deadly disease, the ill that was, to the male homoerotic world of the late twentieth century what so-called venereal diseases had been to previous generations of heterosexuals: the stigma of infamy. Roberto Jacoby recalls that at around that time he ran into Batato going into a subway station on Rivadavia Street. Batato was carrying a bag on his shoulder. “I’m on my way to get screwed by an inmate,” he told Jacoby, a smile on his face. He had come upon an ad put out by prisoners looking for company. “I am a crazy queen—going to get fucked by a killer,” he went on, and then headed down the stairway.

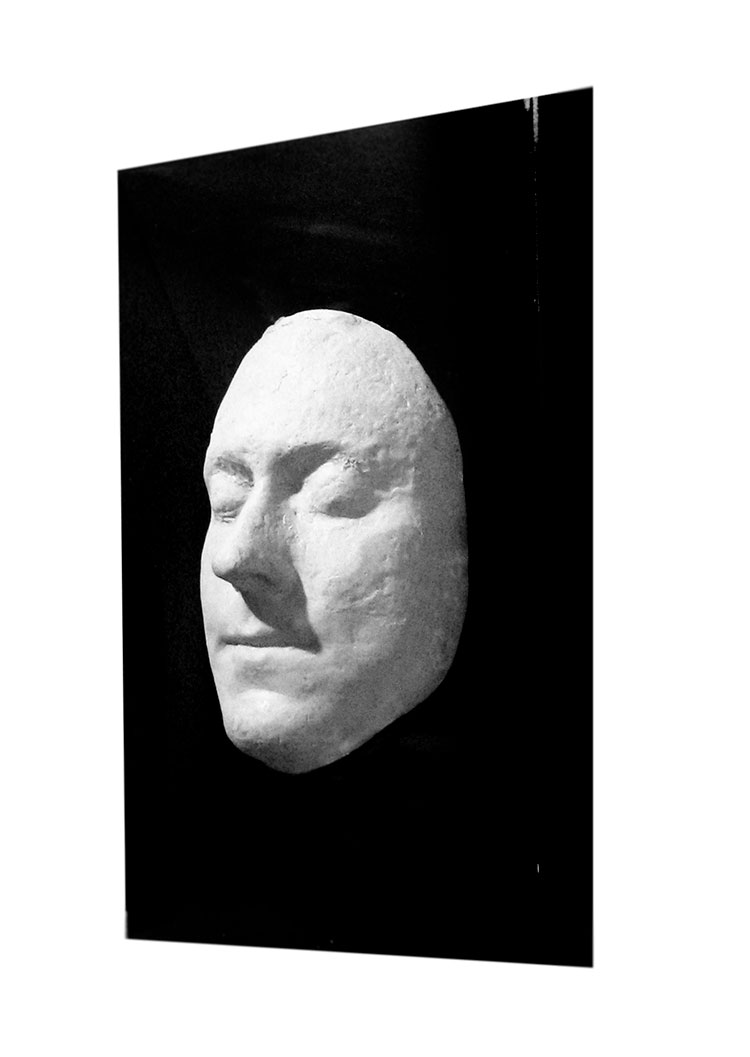

Madness is not only bound to gender nonconformity, but—like AIDS and sexual dissidence—it also acts as a disqualifier, cause for slander, even banishment. And madness is also the instrument Batato uses to bring his alter egos to life, the characters that destroy anything stable, blow up meaning, expose a hidden truth. Batato, then, appears to be the compendium of disgrace, like the saint who longs for shame for the sake of spiritual elevation. Perhaps that injection was the final ordeal, the last station of the cross, the apotheosis of his life-work: Batato died only nine months later. It is not surprising that many remember him as an angel, a pagan angel from the depths of the depths, an artist capable of lifting himself up in marginality through the body—as battlefield, as operation theater, as material on which he etched the story of an erotic and political identity until he finally met his sacrificial fate.

Notes

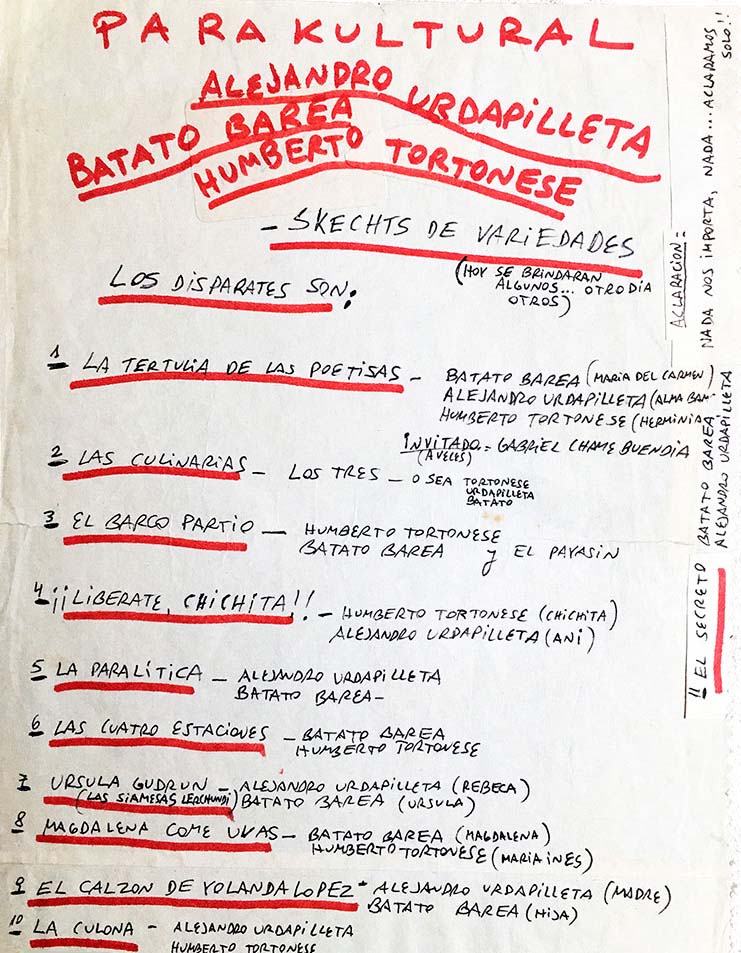

1. On the Parakultural, see Archive 3 below.