If it weren’t for the rage

that keeps baring my fangs

I wouldn’t exist, or so they might say

—Regina José Galindo, Spider Web

In downtown Guatemala City, just a few blocks from the Palacio Nacional, the seat of the executive branch, and the Plaza de la Constitución, is the Correos y Telégrafos building, the central post office. Its distinctive trait is an arch in the neocolonial style that fascinated the military officers who governed the country starting in 1871. With the same dedication they applied to trimming their moustaches, they forced chained Indigenous children, women, and men, by dint of rifle butts, to coffee plantations while they had public buildings, barracks, and cemeteries built. The Arco de Correos, as that arch is called, is one of the many structures built to last that General Jorge Ubico, the dictator who ruled Guatemala for fourteen years (1930–1944) ordered built. Ubico was a regular rapist of women, mostly teenagers (anyone who wanted to get into his good graces knew that the best way to do so was by offering him a sacrificial victim, even if it was one’s own daughter). He would not have been amused, then, when, some five decades after his overthrow, an enraged woman shouted from “his” building poems to be scattered to the winds. It was 1999, and the artist who hung down from the Arco de Correos in a harness sustained by ropes was named Regina José Galindo. The image of that work and her name were not only reproduced in the mass media, but also engraved in the memory of those of us who witnessed an event that re-signified public space. That building was now the one with the arch from which Regina hang (Lo voy a gritar al viento [I Will Shout it to the Wind], performance, 1999).

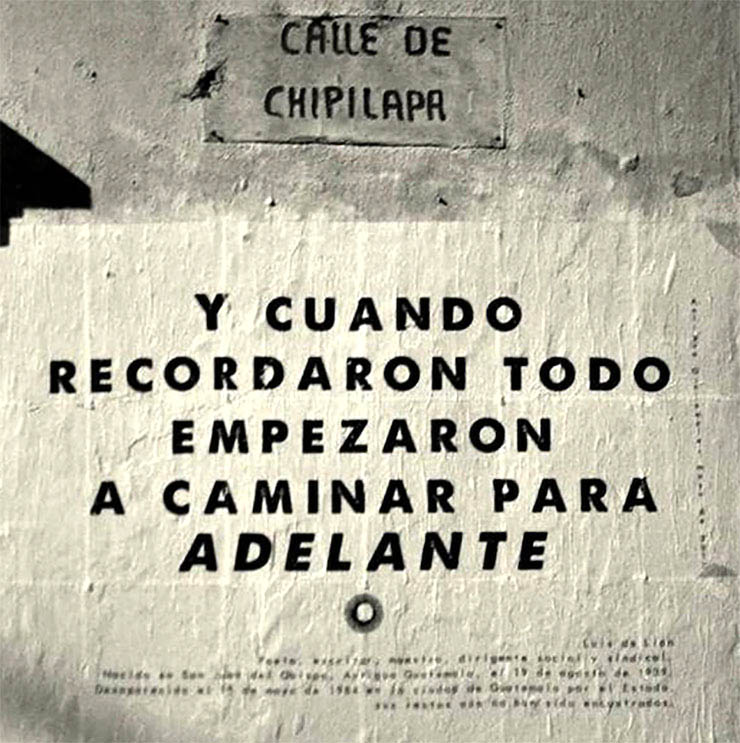

Guatemala was, at that time, a country waking up from a long nightmare. A few numbers attest to the scale of the horror: two hundred thousand dead, forty-five thousand missing, a million displaced, four hundred massacres and about as many villages erased from the map. Three decades of war came to an end when the government and the guerrilla fighters signed a peace treaty. Despite the freedoms won, some artists and writers, Regina among them, looked askance at the incipient peace process. It would take more than a few very old and very uniformed men embracing to fix the country, and decades of terror cannot be undone by signing official documents. The same year Regina hang from the Arco de Correos, Guatemalans, under pressure from the usual suspects—the most reactionary and brutal sectors, the historic beneficiaries of fortunes and privileges in defense of which they committed one of the bloodiest slaughters in the Americas—voted against the constitutional reforms necessary to pave the way for peace. That same year, headlines that attested to rapes and other brutal acts of violence against women committed during the last six months of the twentieth century were projected onto Regina’s nude body (El dolor en un pañuelo [Pain in a Handkerchief], performance, 1999). Even Regina’s early work sensed the future. She was aware that good political intentions—if there ever were any—were not enough to hold back an undercurrent of violence. If El dolor en un pañuelo were performed again today, it would not be a smidgen less relevant. We are just twenty-two days into January, 2021, and already twenty-three women have been murdered in Guatemala—more women dead than days have passed in the new year.

Rituals to sublimate trauma

In the over twenty years since that work, Regina José Galindo’s art has been an oracle, a condemnation, and a daily chronicle of a country and region used to atrocity. And while it’s true that she often turns her attention to topics that go beyond national borders, her point of view seems always to be grounded here, dug like a navel into this land. The themes she addresses are obsessively, tirelessly, the same: violence and injustice, exclusion and inequality, the countless ways we human beings are capable of spreading pain.

There are no indexes to measure “art’s power to change the world”—a grand notion upheld by everyone but artists—and, if they did exist, I would have no interest in or use for them. Nonetheless, every time a new horror joins the long list, we turn to Regina to see how she interprets it, what ethical light will be cast by the most recent symbol she has created. It matters little what specific theme a given performance addresses. What runs through them all is one thing: ethics. And that means that these works question and overwhelm us in identical measure. Just a few examples, a tiny sample from a vast and complex body of work: In 2003, the Guatemalan Constitutional Court illegally authorized General Efraín Ríos Montt, who had participated in coups d’etat, to run for president (ten years later, he would be convicted in a Guatemalan court for having committed genocide against the Mayan Ixil people in 1982). Armed with a recipient full of human blood, Regina walked the distance between that court and the Palacio Nacional. Every so often, she would dip her feet in the recipient in order to leave in her wake, on the cracked pavement of the downtown streets, bloody footprints in memory of the victims of the war (Quién borrará las huellas [Who Will Erase the Tracks?], performance, 2003). On International Women’s Day 2017, fifty-six girls were trapped and burned alive in the Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción, a public shelter for minors where they had endured all order of abuse, including sexual exploitation. The very people who were tasked with protecting the girls decided to ignore the nine full minutes of shouts coming from the locked room where they burned to death. Forty-one died. No one has, as yet, been convicted. Regina and forty other women, among them mothers of some of the victims, locked themselves in a small room and screamed for nine minutes straight. The photographs and audio recording of the work are wrenching (Las escucharon gritar y no abrieron la puerta [They Heard Them Scream and Did Not Open The Door], performance, 2017).

Though all her art begins with herself and consists of her own body—its guts, skin, breathing—though her body is the background and figure of the primordial art she creates, Regina does not waste her time navel- gazing. Her art seems to grow out of the perhaps-never-satisfied desire to break out of the insularity of her own body in order to blend into that greater body of which we all form part. Each one of her performances is a ritual to sublimate our traumas, a spell to light up the dark.

Backward steps

For some years now, a number of knowing voices have warned us, as their own alarms go off, that democracy is in an overt and brazen retreat. That regime organized for pursuit of the common good, where society elects its representatives, where individual rights are respected and institutions held to account for abuse and arbitrariness—democracy—has been taken for granted for the last thirty years (even though it is really an anomaly in the arc of our history). In regions like Central America, that retreat has left unforgettable images: In February 2020, the young president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, burst into Congress with a visibly armed military escort to twist that legislative body’s arm into grant him a loan (he seemed to want to remind us that being a millennial in no way diminishes his authoritarianism). Two years earlier, Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales, who had come to power at the hand of retired military officers active in the darkest years of the war, expelled from the country the United Nations commission investigating cases of corruption (some of them involving Morales himself or members of his family). He did so on national television and, to give the move extra oomph, he was accompanied by the high military command, an image that Guatemalans had not seen on their TV screens since the eighties. In Nicaragua that same year, the police murdered hundreds of people who were protesting against the government of Commander Daniel Ortega—that fossil of the Cold War—and his wife, Rosario Murillo. The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States sped things along. His lies, outbursts, and authoritarian temper tantrums not only deepened polarization and weakened institutions in his country, but also backed and encouraged many would-be dictators, regardless of ideological bent, around the world. The prime example in Latin America is Jair Bolsonaro. And, as if all that weren’t enough, the restrictions imposed to control—or attempt to control—the Covid-19 pandemic sent democracy into retreat even in those countries where it seemed encoded in inhabitants very DNA. According to the Global Democracy Index, an annual report put out by the British weekly The Economist, in 2020 democracy retreated 70% around the world. “The pandemic caused an unprecedented rollback of democratic freedoms in 2020, which led the average indicator to fall to historical lows,” the report states. It is as if authoritarianism had always been there, lurking in presidential offices around the world, waiting for the right moment to hop out and reclaim what had been snatched away from it.

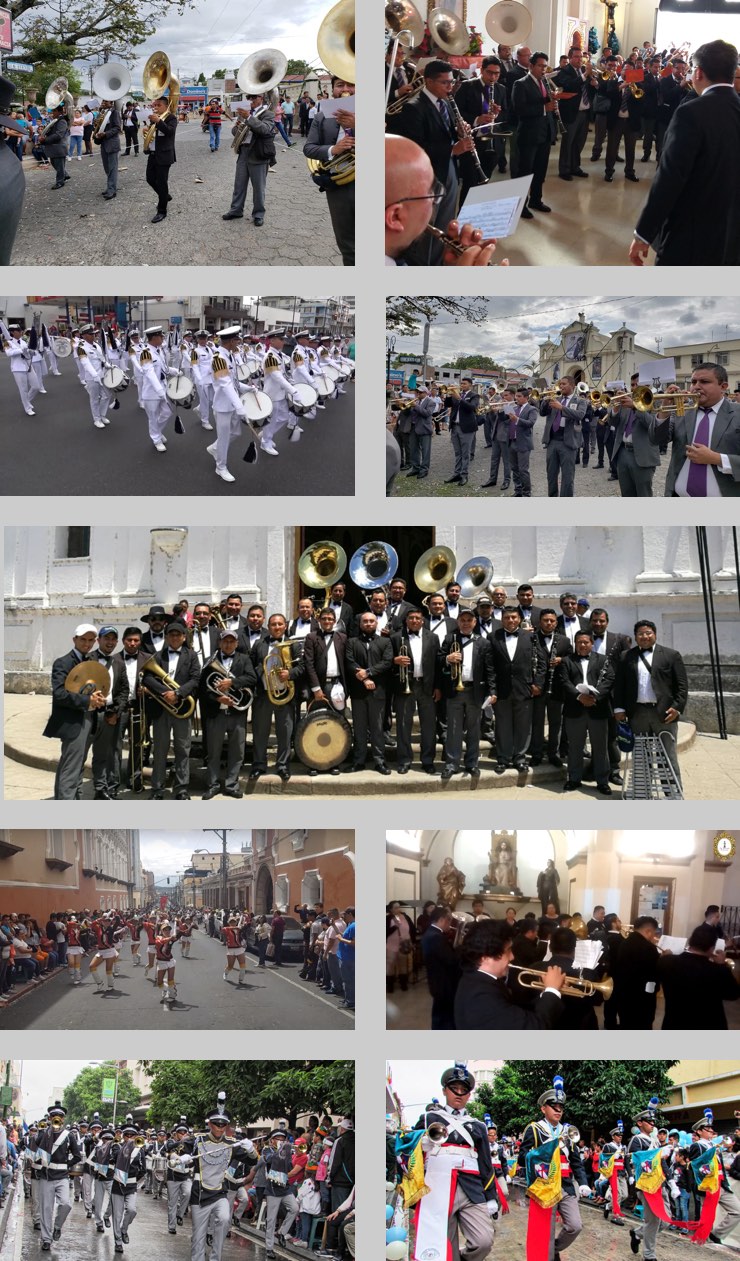

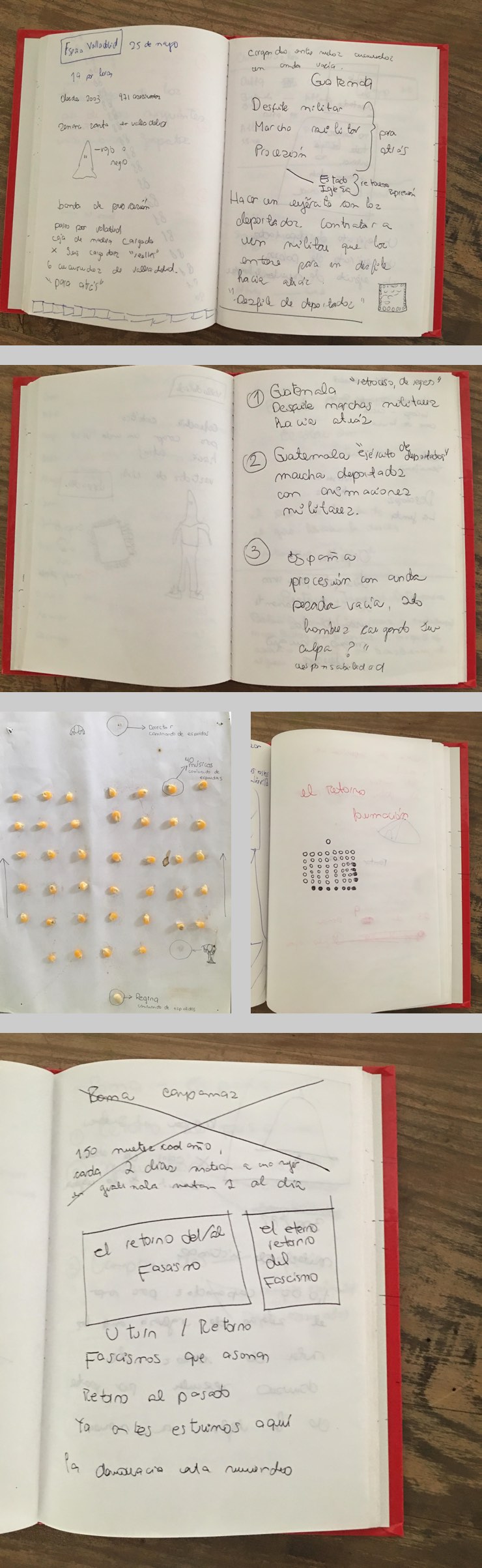

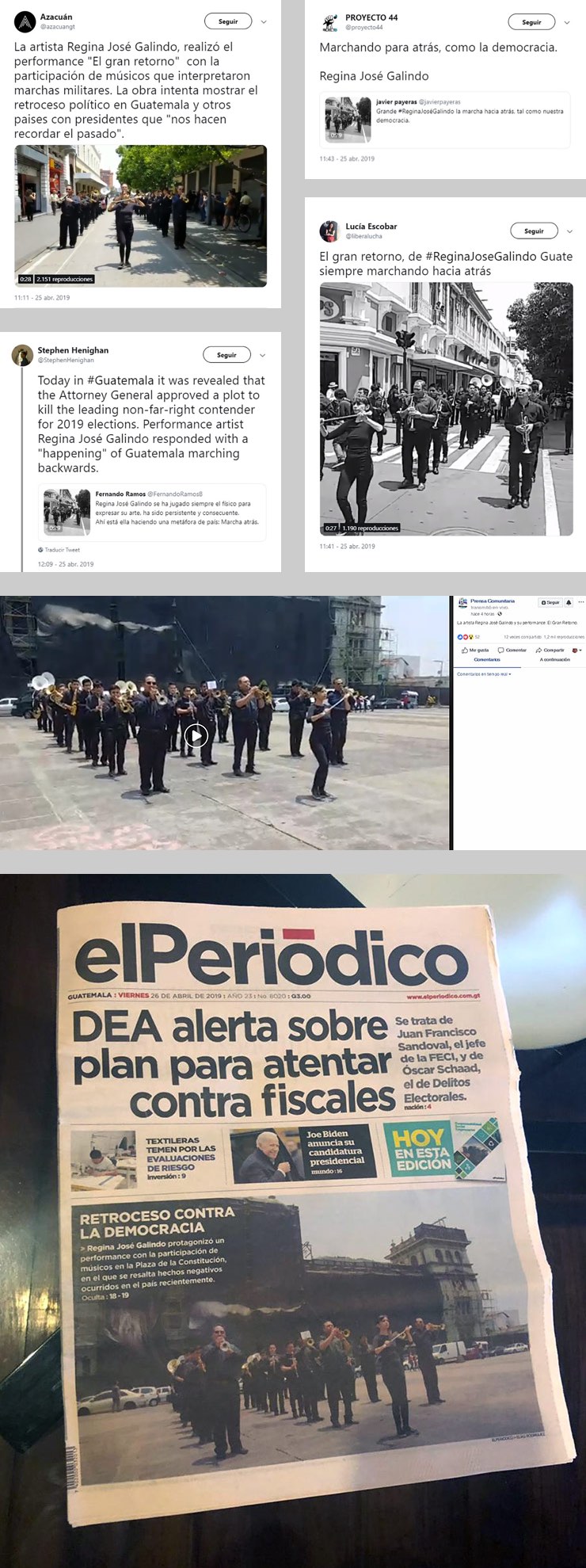

With characteristic economy of resources and ability to create straightforward metaphors, Regina José Galindo imagined a performance whose movements and sounds would capture the pulse of the times. A band of forty-five professional musicians played Guatemalan military marches while they themselves marched backward from the police headquarters to the Palacio Nacional—a path similar to the one taken in Quién borrará las huellas, which makes us think that Regina’s art is also a journey and a map of symbols drawn on the skin of history. And, at the front of the band, looking fiery and engrossed, is Regina, baton twirler and conductor of this staging of our return to the mouth of a wolf we foolishly thought dead. The video of the performance is disconcerting. It takes a while to realize we are not seeing images in rewind (El gran retorno [The Great Return], performance, 2019).

Up to this point, the work speaks for itself. It is worth dwelling on one of its micro-symbolic elements, though, to get a true sense of its complexity. First off, the sounds. If there is one thing that resonates in our shared memory—and this may well hold true for the entire continent—it is the moronic hammering of military marches. In Guatemala, those horns and drum rolls have been the music of power since the late nineteenth century, with the liberal reform. When they don’t remind us of being forced as children to march on Independence Day, they remind us of profusely-moustached toad-jowled generals with medal-laden chests announcing foreign threats, celebrating military coups, or praying to the holy spirit on national television. The path marched by Regina’s band, whose musicians lost none of their verve as they skillfully marched backward, began at the historical police headquarters that today houses as well the Ministry of the Interior. The building was once a Franciscan convent (its treasures were plundered by the aforementioned “liberals” of the 1871 reform). Starting then, and well into the twentieth century, those walls housed the most varied collection of uniformed psychopaths. Perhaps the best example of those individuals was Coronel Germán Chupina Barahona, chief of police during the General Romeo Lucas García administration (1978–1982). Chupina had placed six or seven marimbas, each with its own player, in the lobby of that building—the starting point of Regina’s backward march—so that, during the hours when visitors were received, the music would drown out the screams of the people being tortured in the basement. Regina’s band continued down Sexta Avenida, the city’s main thoroughfare and meeting place. Every September 15, it is marched down, double step, by those school bands that have not yet dared to turn their back. Soon before reaching their final destination, Regina and her band marched by the place where student leader Oliverio Castañeda De León was murdered at the order of Lucas’s Minister of Interior, Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz—also remembered for, among other brutalities, having had a torture chamber in his basement. The spot is marked by a commemorative plaque that hurried passersby rarely stop to look at. Unsuspected doors open when Regina ritualizes the public space. She didn’t get a permit for the march, and yet the police asked no questions. In fact, they stopped traffic at some corners to let the parade go by “without incident.” Finally, they reached the end of their journey, the Palacio Nacional—its name today, with unwitting cynicism, ends in “of culture.” This is the building where Jorge Ubico, the dictator ousted by the Revolution of 1944 who had ordered the construction of the Arco de Correos, must have dreamed of ending his days surrounded by laurels and bathing in the gratitude of his people.

El gran retorno is a reminder of our helplessness. Marching backward seems like an act of resignation. The triumphant, almost festive, music only deepens, through contrast and irony, the hopelessness. Let’s hope this time Regina’s work does not predict the future so accurately. Let’s hope that El gran retorno is only a warning. In the meantime, we will continue to celebrate the uncomfortable allure of an artist and a work that do not countenance indifference.